We headed along a path to the grapes. In a quiet corner hidden by trees, grape vines were growing. Spread over a metal frame, they formed a green shelter. Inside the shelter the ground was covered with soft, green grass. Peace reigned in there, and from the shelter’s green twilight the whole world looked green. We spread out on the grass… ‘This is where our school begins. From here we will look out at the blue sky, the orchard, the village, and the sun’.1Vasily Sukhomlinksy, My Heart I Give to Children, trans. Alan Cockerill (Graceville: 2016), 31.

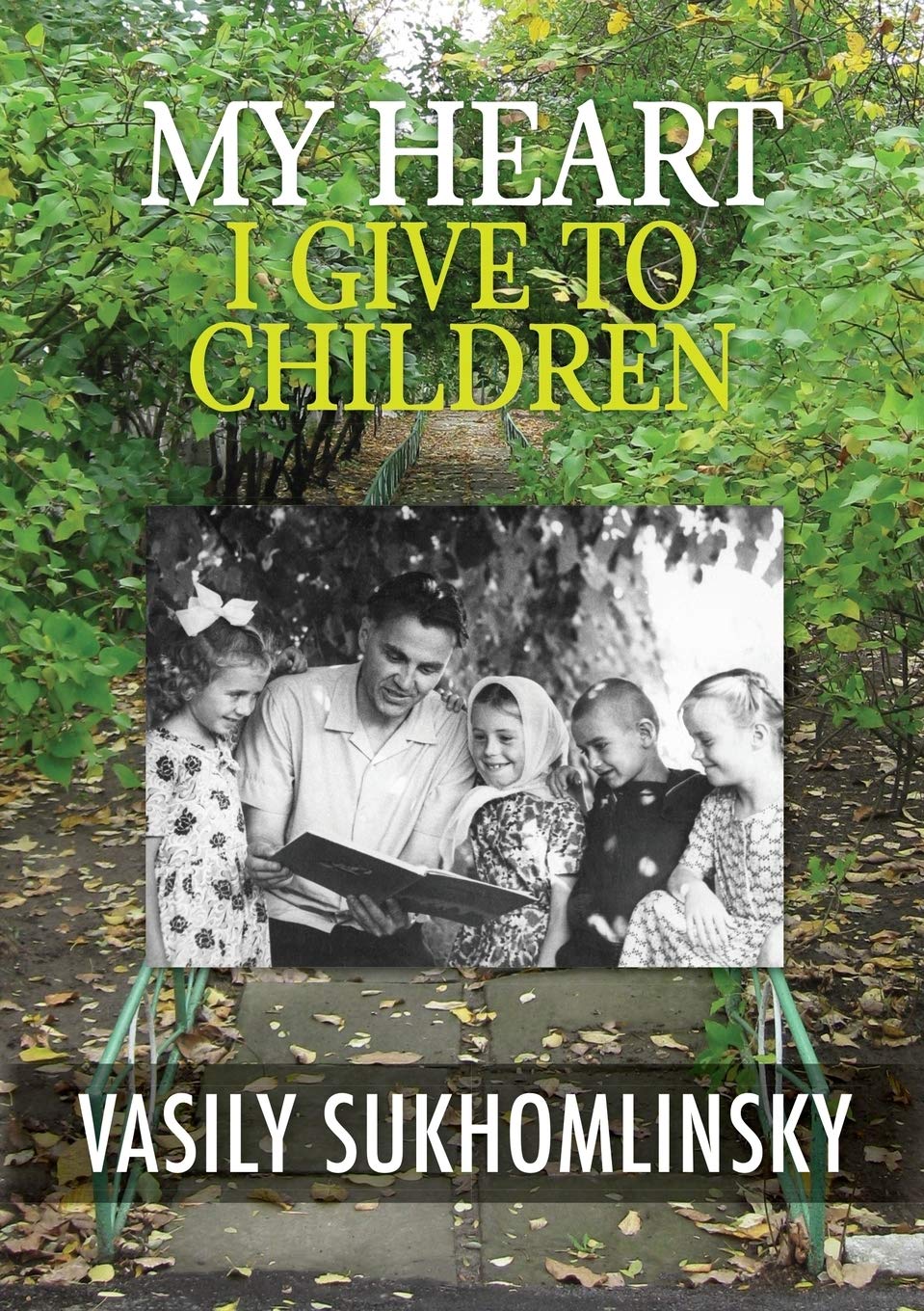

Born in 1918 to a peasant family in the small village of Vasilievka, Ukraine, Vasily Sukhomlinsky became a pioneer of holistic education in the Soviet Union2The Russian term used for holistic education is “vsestoronnee razvitie”, which refers to the “all-round development” of the student; see: Alan Cockerill, Each One Must Shine (2009), 25. and “the most influential Soviet educator of the 1950s and 1960s.”3Alan Cockerill, Translators Introduction. In: My Heart I Give to Children, trans. Alan Cockerill (2016), x. At this time, Sukhomlinsky “was at the forefront of public interest”, his works were being translated across the world, and he was “awarded almost all the honours that can be paid to an outstanding educationist.”4Simon Soloveichik, “Sukhomlinsky’s Paradox” In: V. Sukhomlinsky On Education (Moscow: 1977), 7. Overall, Sukhomlinsky wrote 30 books, 500 articles, and around 1,200 children’s short stories.5Simon Soloveichik, “Sukhomlinsky’s Paradox” In: V. Sukhomlinsky On Education (Moscow: 1977), 7.

Sukhomlinsky was seriously injured while fighting in the Second World War, and in 1942 was sent to a military hospital in the western Urals (where he spent much of his time as a principal of a secondary school in Uva). When he returned to Onufrievka (the district centre for his village of Vasilievka) he was appointed the district head of the Department of Education, overseeing the regeneration of education in a region that had been devastated by the Nazi occupation. And in 1948, he was appointed principal of a combined primary and secondary school in the nearby town of Pavlysh, a position he held until his untimely death in 1970 aged only 51. Since that time, Sukhomlinsky’s important work slowly faded from the pedagogical canon, and his legacy underwent the subtle anti-Communist distortions so characteristic of the post-Soviet era.

My Heart I Give to Children (1968) is a relatively late work from this esteemed educator. Many of his earlier works remain untranslated and other later works remain unpublished. As one of the only available English translations, the book offers a rare insight for English readers into Sukhomlinksy’s extraordinary pedagogical program. Although it was originally published in the German Democratic Republic (or East Germany) in 1968, with the first Soviet edition appearing a year later in 1969, this review uses the most widely available English translation, published and translated by the Australian educator and linguist Alan Cockerill in 2016.

The book is split in two main parts. Part one explores the development of the Pavylsh School’s first pre-school class in 1951. The second part follows this class as they progress through their primary school years. Rather than interrogate the distinction between pre and primary education, this review seeks to capture the soul of Sukhomlinsky’s pedagogical vision which combined nature and fairy-tales with academic and aesthetic education. Before we begin the journey into the fairy-tale landscape of rural Ukraine, however, it is important to first confront the ghosts that haunted this otherwise idyllic scene.

The Long Shadow of War

The war has left deep scars, wounds that have not yet healed. These children were born in 1945, some in 1944. Some of them became orphans while still in their mother’s womb.6Vasily Sukhomlinksy, My Heart I Give to Children, trans. Alan Cockerill (2016), 19.

The chapter My Students’ Parents illustrates Sukhomlinsky’s keen awareness of the devastating impact of the Second World War on communities, and especially children, across the Soviet Union. Here he documents the complex ways that families had been traumatised and how this was reflected in the souls of the children. “The greatest trauma for many of these children’s hearts”, he writes, “was that they had been exposed to evil too early in life… darkening their joys, hardening their souls, convincing them that people were bad and that there is no truth in the world”.7Vasily Sukhomlinksy, My Heart I Give to Children, (2016), 19.

Sukhomlinsky himself was no stranger to such trauma. Immediately after graduating from the Poltava Pedagogical Institute at the age of 23, he joined the Red Army to fend off the advancing Nazi army. Sustaining a serious shrapnel wound near Rzhev in 1942, that would trouble him the rest of his life, Sukhomlinsky returned home to his own tragedy. While on a mission with partisans in Nazi occupied Ukraine, his wife Vera was captured and imprisoned. In prison she gave birth to the couple’s first child but after refusing to give up the names of her detachment, Vera was tortured, her newly born son killed in front of her, and she was eventually hanged.8“From the Publishers” In: To Children I Give My Heart, trans. Holly Smith (Moscow: 1981), 2 In a separate article, the book’s translator, Alan Cockerill, writes: “For years he found it difficult to sleep at night, and woke early to lose himself in his work. His love for children was what kept him sane. Each morning he looked forward to the sound of their chatter as they arrived at school.” My Heart I Give to Children must be considered against this tragic backdrop. What emerges from its pages is a story of a community torn apart by the horrors of war, who then found a path to collective transformation through Sukhomlinsky’s healing pedagogy of nature.

A Pedagogy of Nature

“Man lives on nature – means that nature is his body, with which he must remain in continuous interchange if he is not to die. That man’s physical and spiritual life is linked to nature means simply that nature is linked to itself, for man is a part of nature.”9Karl Marx, “Estranged Labour”, Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844

In Nature: The Source of Health, Sukhomlinsky illustrates the impact of the environment both on children’s health and cognitive development. There are several fascinating insights in this chapter, ranging from diet and bees to eyesight and solar radiation. But two themes that demonstrate Sukhomlinsky’s attempt to reconcile man with nature are exhibited most clearly in his understanding of phytoncides and fairy-tales.

Phytoncides: An Elixir of Health

“Air saturated with the phytoncides of grasses (wheat, rye, barley, buckwheat and meadow grasses)”, Sukhomlinsky writes, “is an Elixir of health.”10Vasily Sukhomlinksy, My Heart I Give to Children, trans. Alan Cockerill (2016), 58. As such, not only did he take his students on long walks through the fields and woods to breath in the air infused with these phytoncides, but he also advised parents to plant certain trees (usually nut trees) near their children’s windows, to provide constant exposure to phytoncides in their early years.

‘Phytoncide’ is now used as “a generalized term for natural chemicals released by plants into the environment”,11Craig et al. “Natural environments, nature relatedness and the ecological theater: connecting satellites and sequencing to shinrin-yoku”, Journal of Physiological Anthropology, 35:1, 2016, 2. to defend themselves from attack by herbivores and decay.12Zhu, S-x.; Hu, F.-f.; He, S.-y.; Qiu, Q.; Su, Y.; He, Q.; Li, J.-y. “Comprehensive Evaluation of Healthcare Function of Different Forest Types: A Case Study in Shimen National Forest Park, China” Forests, 12:207, 2021, 2. However, literature on these natural phenomena was almost entirely absent during Sukhomlinsky’s lifetime, which begs the question, where did he encounter this concept?

It seems likely that Sukhomlinsky was drawing on the work of pioneering Soviet biochemist Dr Boris Tokin. After coining the term “phytoncide” in 1928, Tokin went on to publish the book Phytonzide in 1956. Tokin demonstrates the “astonishing biological effects of herbal ingredients and fascinating possibilities of the practical use of these phenomena”.13Christoph Richter, “Phytonzidforschung—ein Beitrag zur Ressourcenfrage” (“Phytoncide research – a contribution to resource questions”), Hercynia N.F. 24:1, 1987, 95. For example, Tokin found that a “drop of water infused with spruce, fir or pine needles added to a drop of water containing protozoa (parasites) will kill them [the parasites] instantly” [authors translation].14Craig et al. “Natural environments, nature relatedness and the ecological theater: connecting satellites and sequencing to shinrin-yoku”, Journal of Physiological Anthropology, 35:1, 2016, 3. Put simply, in discovering phytoncides, Tokin’s work unveiled a broad relationship between natural air and processes of decay.

These remarkable findings were largely ignored until a revival in the 1990s; a project fuelled by interest in the “hygiene hypothesis”. Based on a 1989 British Medical Journal article, the hygiene-hypothesis states that the industrialised world had seen a rise in allergic diseases (e.g., hay-fever) as a result of the “diminished opportunity for early-life exposure to pathogenic (and diverse commensal) microbe exposure via increased hygiene, antibiotic use, smaller family sizes and lower exposure to bacteria in foods, and the overall environment.”15Craig et al. “Natural environments, nature relatedness and the ecological theater: connecting satellites and sequencing to shinrin-yoku”, Journal of Physiological Anthropology, 35:1, 2016, 3.

This rise in allergic diseases, however, has not been observed to the same extent in the non-industrialised world,16William Parker & Jeff Ollerton, “Evolutionary biology and anthropology suggest biome reconstitution as a necessary approach toward dealing with immune disorders” Evol Med Public Health, Jan 2013,1, 90. leading analysts to conclude that urbanisation not only leads to the loss of macro-biodiversity (building industrial cities necessitates extinguishing plant life) but is also linked to the loss of microbial diversity previously symbiotic with the human body. Phytoncides are considered key constituents of this microbial biodiversity,17Craig et al. “Natural environments, nature relatedness and the ecological theater: connecting satellites and sequencing to shinrin-yoku”, Journal of Physiological Anthropology, 35:1, 2016, 3. and are said to have anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antifungal, analgesic, and anti-stress properties.18Zhu, S-x.; Hu, F.-f.; He, S.-y.; Qiu, Q.; Su, Y.; He, Q.; Li, J.-y. “Comprehensive Evaluation of Healthcare Function of Different Forest Types: A Case Study in Shimen National Forest Park, China” Forests, 12:207 (2021), 2. This growing body of research now represents “a cornerstone of immunology”.19William Parker, “The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ for allergic disease is a Misnomer”, BMJ (2014) These recent studies demonstrate both Sukhomlinsky’s sharp scientific mind and his understanding of the symbiotic relationship between man and nature or, as Marx would have it, man as nature. Indeed, when he wrote that phytoncides are an “Elixir of health”, he had to some extent anticipated the next 50 years of western environmental anthropology and immunology.

The health benefits of nature could not, for Sukhomlinsky, be an end in themselves however. They were instead a component part of a more complex pedagogical program in which the health of the child was dialectically related to their cognitive development. The health benefits of nature filled children with a “life giving energy”, that allowed them to develop their intellectual and creative endeavours to their full potential.20My Heart I Give to Children (2016), 56.

But nature had another function. “Most importantly,” writes Sukhomlinsky, “children must be taught to think in the midst of nature, at that life-giving wellspring of thought from which streams of living water constantly flow”.21My Heart I Give to Children (2016), 36. Monsters and myths, suns and moons, good vs evil, nature also held the key to the magical land of fairy-tales and dialogical education.

Fairy-tales and Freire

‘The Sun is scattering sparks’, said Katya softly. The children could not tear their eyes away from the enchanting world, and I began to tell them a story about the sun.22My Heart I Give to Children (2016), 32.

From here, Sukhomlinsky drew upon his student Katya’s spectacular image of the sun scattering its cosmic sparks by telling the children a tale of two giant blacksmiths and a golden anvil, all the while sketching a picture in his notebook, bringing the story to life. After a moment of silence there came a flurry of questions from the youngsters. “Dear children,” came his reply, “I will tell you all that another time”, leaving the curious minds yearning for their next lesson. Deeply moved by the spontaneity of this mutual dialogue, that night Sukhomlinsky went home and dreamt about the silver sparks of sunlight, and he was inspired: “I would introduce the little ones to the surrounding world in such a way that every day they discovered something new in it, so that every step led us on a journey to the wellsprings of thought and speech, to the wondrous beauty of nature”.23My Heart I Give to Children (2016), 34.

Sukhomlinsky’s re-presentation of Katya’s scattering sparks, not through the sanitised language of adults, but through the children’s own language of fairy-tales is an example of Paulo Freire’s dialogical method par excellence. For Freire, “liberating education consists in acts of cognition, not transferrals of information.”24Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, trans. Myra Bergman Ramos (New York and London, 2005), 79. Thus, a liberatory educator should follow a “dialogical” and “problem-posing” pedagogy. This is:

… constituted and organized by the students’ view of the world, where their own generative themes are found. The content thus constantly expands and renews itself. The task of the dialogical teacher in an interdisciplinary team working on the thematic universe revealed by their investigation is to “re-present” that universe to the people from whom she or he first received it—and “re-present” it not as a lecture, but as a problem.25Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, trans. Myra Bergman Ramos (New York and London, 2005), 109.

For Sukhomlinsky, although nature was important, it had to be animated by stories, for “without stories the surrounding world is just a beautiful picture painted on a canvas. Stories bring that picture to life.”26My Heart I Give to Children (2016), 35. However, when combined with fairy-tales, nature offers the optimum environment for the realisation of a dialogical pedagogy. During the day, the children had made up and heard several stories. Some about the blacksmiths, and others about the sun’s mystical garland. As the sun was setting, one child, Lida, asked, “The blacksmiths have brought the sun its silver garland… Where does it put yesterday’s garland?” After a moment of silence, a quiet child, Fedya, offers the teacher a helping hand: “The garland has melted across the sky.” Sukhomlinsky builds his final story of the day around this image, finishing his narrative: “Soon the sun will enter its magic garden, and the stars will come out.”

“What are stars? Why do they come out? Where do they come from?”, another colourful avalanche of problem-posing curiosity from “those little researchers and explorers of the word.”27My Heart I Give to Children (2016), 20-37.Nature, fairy-tales, and cognitive development are dialectically related; nature both inspires and requires the story, but for Sukhomlinsky the fairy-tale has its own unique purpose too:

Children see living images and then imaginatively recreate those images in their own representations. The viewing of real objects and the creation of imaginative representations of those objects: there is no contradiction in these two stages of the cognitive process. The fantasy image in a story is interpreted by a child, and created by that same child as a vivid reality. The creation of fantasy images provides fertile ground for the vigorous development of thought processes. 28My Heart I Give to Children (2016), 50.

Combined with a dialogical pedagogy, sharing in children’s fantastical world of fairy-tales is an important practice for progressive educators. Again, although primarily concerned with adult literacy, Freire shared this view of child education. Drawing on the work of his daughter Madalena Freire in her book on child education, A Paixão De Conhecer O Mundo [The Passion to Know the World] (1994), Freire asserts: “Teachers must be able to play with children, to dream with them. They must wet their bodies in the waters of children’s culture first. Then they will see how to teach reading and writing.”29Paulo Freire, “Reading the World and Reading the Word: An Interview with Paulo Freire.” Language Arts, 62:1 (1985), 18.

Twelve years after musing that “the sun is scattering sparks”, Katya wrote an essay about her homeland and repeated this phrase to describe her love of nature.30My Heart I Give to Children (2016), 35. Stories, therefore, leave an indelible mark on the consciousness of the child, conjuring up permanent fantasies that they too can pass on like Sukhomlinksy taught them. As he concludes: “In my view the main aim of our whole system of education was to teach people to live in the world of the beautiful, so that they could not live without beauty, so that the beauty of the world created an inner beauty. 31My Heart I Give to Children (2016), 72.

Although they capture some of the essence of Sukhomlinksy’s pedagogy, a focus on phytoncides and fairy-tales hardly scratches the surface. Art, music, caring for animals, collective farming, these are no less important elements that constituted daily life in the Secondary School of Pavlysh and offer important lessons in prefiguring a revolutionary educational system.

Sukhomlinsky’s compelling analysis of the dialectical relationship between nature, fairy-tales, and education is illustrative of a specifically communist pedagogy. It is interesting, therefore, that the book’s translator, Alan Cockerill, attempts to distance Sukhomlinsky from the Soviet system which allowed such a vision to flourish. Such a revision of Sukhomlinsky’s ground-breaking work in communist education requires some attention.

Ideological Distortion

Editing documents to increase popularity and readership is of course nothing new. The process of publishing any book or article anywhere in the world will go through an editorial process of some kind. While much of this can be innocent (sharpening arguments, checking for errors, etc,), there have been major exceptions. The erasure of Islam from the poetry of Rumi is a particularly notable example of ideological and cultural distortion, a sanitised version used to soothe the Western liberal gaze and reproduce orientalist tropes of Islam. But what is the case for My Heart I Give to Children?

In the introduction to the 2016 edition the translator, Alan Cockerill, outlines various aspects of his translation which are worth considering in detail. Cockerill’s translation is based on the 2012 re-publication of the book by Sukhomlinsky’s daughter, Professor Olga Sukhomlinskaia. Cockerill argues this edition, based on an unpublished 1966 manuscript, contains “less material of an ideological nature (which was included in the first edition in response to editorial pressure)”. The 2012 edition also contained material from the 1969 Soviet version but as revisions in footnotes (as a commentary to identify the editorial changes between the 1966 manuscript and 1969 publication).32My Heart I Give to Children (2016), xiii. Cockerill’s translation does not contain a commentary on these missing elements leaving the reader to question what “material of an ideological nature” has been removed and, importantly, why? This section starts to illuminate the problem.

Cockerill gives us some indication of his own ideological standpoint in his 1999 biography of Sukhomlinksy, Each One Must Shine. For Cockerill, Sukhomlinksy’s life and educational work are split across three main eras: Stalinism, the Khrushchev “thaw”, and post-Khrushchev authoritarianism. It is during the thaw years that Cockerill suggests that Sukhomlinsky’s views were “maturing and becoming more liberal” which “brought him into conflict with party ideologues.”33Alan Cockerill, “Sukhomlinsky’s German Connections: The Publication of My Heart I Give to Children in 1968 Berlin” in Cossacks in Jamaica, Ukraine at the Antipodes: Essays in Honor of Marko Pavlyshyn, edited by Alessandro Achilli, Serhy Yekelchyk and Dmytro Yesypenko, (Boston: 2020), 530. This period is juxtaposed most significantly against those of the so-called Stalinist era, with Cockerill branding Stalinist education as “authoritarian in the extreme”, following a “uniform syllabus” with a strong focus on standardised lessons and textbooks.34Alan Cockerill, Each One Must Shine, (Sydney: 2009), 197. It is true that the educational reforms of the 1930s took a sharp turn away from the pedagogical experiments that characterised the 1920s. Due to generations of Tsarist underdevelopment and the looming threat of Nazi invasion, the Soviet Union was under intense pressure to industrialise and thus required a steep uptick in specialists across the country. Perhaps Cockerill would disagree with this view, but what does Sukhomlinsky have to say on the subject? After reading educational reforms planned for 1958, Sukhomlinsky wrote this letter to Khrushchev that same year:

The decisions taken by the Party’s Central Committee during the ’thirties concerning work in schools, were essential at the time. They played an important role in the development not only of our country’s culture, but of its whole national economy. They were directed at strengthening knowledge of the foundations of science and scholarship, they put an end to all sorts of hair-brained schemes to replace a systematic course in secondary education with ‘complexes’ and ‘projects’. Thanks to the implementation of these decisions a cultural revolution was effected in our country. There is more good than bad in the fact that there are 2.5 million people in our country at the present time, who have completed secondary school but not embarked on tertiary studies.35Alan Cockerill, Each One Must Shine, (Sydney: 2009), 158.

Consequently, it appears that one of the main “party ideologues” that Sukhomlinsky was coming into conflict with was the same one that Cockerill has praised as being most closely aligned to Sukhomlinsky’s humanistic values. Given Sukhomlinsky’s vast body of work, one could perhaps be forgiven for missing this crucial insight. But this letter is pulled directly from Cockerill’s biography itself.

Cockerill further argues that Stalinism was a “return to Tsarist goals and methods” and “bore closer resemblance in its political culture to the Church States of medieval Christendom or to the Russia of the tsars, than to modern pluralistic societies in the West.”36Alan Cockerill, Each One Must Shine, (Sydney: 2009), 139-40. His analysis of Stalinism is drawn almost exclusively from Robert Tucker’s account, which is not so much concerned with numbers and data but is rather a wholly rhetorical critique of the Soviet Union from 1921-1953. Sticking to educational developments alone, it might surprise Cockerill that literacy rates in the Soviet Union jumped from 57.6% to 99.3% from 1920 to 1959 (with a rapid increase specifically from 1926 to 1939, where it grew from 71.5% to 93.5%). More relevant to his point about the supremacy of Western democracies, by 1959 the Soviet Union had a higher average literacy rate for men and women (98.3%) than Britain (98%), the United States (98%), and France (96%).37Boris Mironov. “The Development of Literacy in Russia and the USSR from the Tenth to the Twentieth Centuries.” History of Education Quarterly 31:2 (1991), 229-52 Perhaps the people of medieval Christendom were more literate than we realise?

Ultimately, however, the most revealing accusation is made in relation to the purges, in which Cockerill concludes: “The purges also served to eliminate many liberally-minded intellectuals from the leadership echelons, replacing leaders of middle-class origin with ones of peasant stock.”38Alan Cockerill, Each One Must Shine, (Sydney: 2009), 140. An interesting claim from a defender of “modern pluralistic societies.” For Cockerill, 1966 saw the end of the thaw and a return to Stalinist dogma. It’s here that Cockerill suggests that a state campaign was launched against Sukhomlinsky in 1967 for his essay “Idti vpered! [Let us go forwards!]”. The attack against Sukhomlinsky came from an article in Uchitel’skaia gazeta [The Teacher’s Newspaper] entitled ‘We need a campaign not a sermon’ by B. Likhachev, a lecturer at the Vologda Pedagogical Institute. Likhachev accused Sukhomlinsky of “abstract humanism” and of departing from the pedagogy of Anton Makarenko. As the first educator to elucidate the theoretical underpinnings of collective pedagogy, Makarenko was considered a Soviet hero, thus departing from him was tantamount to anti-Communist betrayal. However, after Makarenko’s death a certain orthodoxy took hold of his teachings, which were sometimes used to promote student discord. Rather than being a critique of Makarenko, who Sukhomlinsky’s lists as his major inspiration, it was instead a critique of this orthodoxy.

Two responses in favour of Sukhomlinksy and against the baseless claims of Likhachev were published by A. Levshin in Literaturnaia gazeta [The Literary Newspaper] and F. Kuznetsov in Literatura v shkole [Literature in the School] that same year, with Sukhomlinksy penning his own response in Literaturnaia gazeta. Indeed, even following the attacks in Uchitel’skaia gazeta: “Sukhomlinsky himself was given space to present his views on the pages of Komsomol′skaia Pravda, Izvestiia, and Pravda, official newspapers of the Communist Youth League, the Soviet government, and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union respectively”.39Alan Cockerill, “Sukhomlinsky’s German Connections: The Publication of My Heart I Give to Children in 1968 Berlin” in Cossacks in Jamaica, Ukraine at the Antipodes: Essays in Honor of Marko Pavlyshyn, edited by Alessandro Achilli, Serhy Yekelchyk and Dmytro Yesypenko, (Boston: 2020), 534. Any sober analysis indicates that there was significant support both from individual academics and major news outlets of the Soviet state, a state which by this point had ostensibly shifted back into Stalinism. As such, it is curious that the above evidence is presented by Cockerill himself.

Finally, what did Cockerill remove from the 1966 manuscript, supposedly the truest illustration of Sukhomlinsky’s views, untouched by communist authorities? In fairness to him, Cockerill does identify the sections he removed with three asterisks, thus leaving the reader to fill in the gaps. To illustrate one of these omissions I rely on Holly Smith’s 1981 translation, To Children I Give My Heart.

In the chapter entitled On the Threshold of an Ideal Life, Sukhomlinsky discusses the importance of moral role models for children. Here, Cockerill includes the brave story of the Polish educator of the Warsaw Ghetto, Janusz Korczak, who refused his own freedom, choosing instead to accompany the children to Treblinka, to calm them and mitigate the horror they were about to face. What is left out, however, are the numerous mentions of Lenin and other Soviet heroes who inspired the children and were, in Sukhomlinsky’s view, just as important as the sacrifices made by Janusz Korczak. For example:

The children were seized by joyful excitement when they heard the story of how, during the difficult years of the Civil War and the years of devastation, Lenin showed great concern for orphans. I wanted Leninist humanity to enter the lives of the children as a great moral value…40To Children I Give My Heart, trans. Holly Smith (Moscow, 1981), 2

Cockerill is of course correct, Lenin’s concern for orphans (and children more broadly) is an overtly ideological position. Not all societies give due attention to the care of their children. But why must it be wiped from the record? Surely anyone concerned with the rights of children should be aware of the ideological currents that seek to establish such rights and made great strides in doing so?

The effect of such redactions paint Sukhomlinsky’s communist views as essentially circumstantial. For Cockerill, he was largely misinformed or confused, a product of his Stalinist upbringing, navigating his trauma of the Second World War, trying to reconcile his humanist values within the limits of an otherwise oppressive communist state. In other words, Sukhomlinsky’s pedagogical intervention owed everything to his personal vision of humanistic education rather than resulting from the influence and guiding ethos of Soviet pedagogy. Cockerill consummates this view by suggesting that Soloveichik, the primary Soviet journalist who popularised Sukhomlinsky’s work after his death, “considered that Sukhomlinsky was a genius who owed his best ideas not to Soviet pedagogical science, but to his love for children and his own natural talent as a teacher, working as he did in relative isolation.”41Alan Cockerill, Each One Must Shine, (Sydney: 2009), 75. On the one hand, it is revealing that such an authoritative claim comes with no accompanying citation. On the other, it appears to be in direct contradiction to Cockerill’s own understanding of Soviet pedagogy. Cockerill admits that “Soviet views of education through the collective (and Western interpretations of Soviet practice) have been formed principally under the influence of [Anton] Makarenko’s ideas.”42Alan Cockerill, Each One Must Shine, (Sydney: 2009), 92. It is interesting then that Soloveichik quotes Sukhomlinsky as saying:

“There is no other teacher whose work I have admired and respected as much as Makarenko’s. It was in his works that I sought true wisdom of which I was so desperately in need. All my modest experimentation in teaching has been a result of that search”.43Simon Soloveichik, “Sukhomlinsky’s Paradox” In: V. Sukhomlinsky On Education, (Moscow: 1977), 32.

Clearly Sukhomlinsky was driven by a profound love for children, but that does not negate his training in the Soviet pedagogical sciences, which were formed, as Cockerill himself suggests, around the principles of Sukhomlinsky’s primary inspiration, Makarenko. Sukhomlinsky is then, in fact, wholly illustrative of the Soviet educational system, which he dedicated his life to upholding and developing.

Guided By Love

The ideas of the Great October Socialist Revolution are the source of one of the New Man’s most important and valuable qualities – his orientation towards the future.44Vasily Sukhomlinsky, On Education, Moscow: 1977), Compiled by S. Soloveichik, 51.

Although his life was cut short by shrapnel fragments from his wartime injury entering his heart at the age of 51, Sukhomlinsky left behind several lifetimes of wisdom, stretching far beyond the field of education as we know it. Grounded in a revolutionary ecological pedagogy, My Heart I Give to Children offers a radical alternative for prefiguring communist education. With a number of his works remaining either unpublished or untranslated, My Heart I Give to Children contains only a snapshot of the pedagogical vision of this extraordinary educator and a guide to navigating the enduring legacy of 1917. Given Cockerill’s spurious analysis of this Bolshevik educator, and at a time of mounting ecological and political crises, a more accurate appraisal of Sukhomlinsky’s life and work is a project of great importance.

“At the risk of seeming ridiculous,” Che Guevara suggested, “the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love.” Vasily Sukhomlinsky stands out as a fearless defender of this maxim.

Alex Turrall is an independent researcher and primary school teacher.

The author wants to thank Martin Jensen for helping them think through the approach to analysing Stalinism. Editing is a pedagogical process, and for this they been very fortunate to have Louis Allday’s kind and patient guidance through writing this review.