Imperialism and fascism march hand in hand; they are blood brothers.1Quoted in Michele L. Louro, Comrades Against Imperialism: Nehru, India, and Interwar Internationalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 238.

These are the words of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of independent India and a longstanding political colleague of Rajani Palme Dutt (1896-1974), the leading theoretician in the Communist Party of Great Britain. In his day Dutt was one of the most influential communists in the English-speaking world, primarily known for his analysis of colonial underdevelopment, but his magnum opus was his full-length study of the rise of fascism.2John Callaghan, Rajani Palme Dutt: A Study in British Stalinism (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1993), 7.

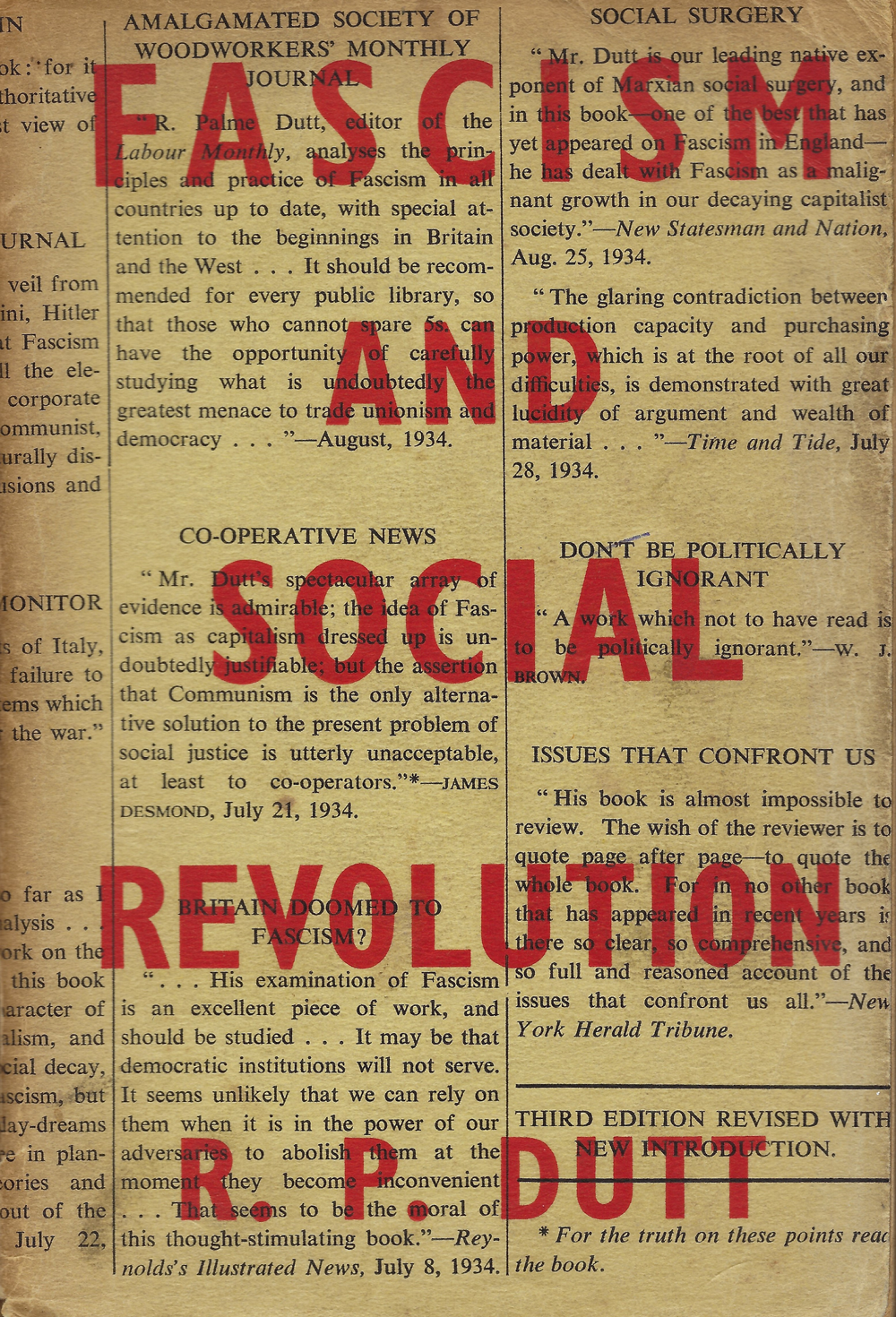

Intended as a sequel to Lenin’s Imperialism, Dutt’s Fascism and Social Revolution (1934) is remarkable for its global perspective, locating the conditions of fascist ascendancy in the “intensified conflict of the imperialist powers”.3R. P. Dutt, Fascism and Social Revolution (Revised 2nd ed., London: Martin Lawrence Ltd., 1935), 63. The imperial dimension of fascism, and its continuities with liberal colonialism, have only recently begun to receive serious scholarly attention. Yet Dutt is absent from the most notable published collection of interwar Marxist writings on fascism, and he does not even get a mention in Trotskyist historian David Renton’s newly revised classic Fascism: History and Theory.4David Beetham ed., Marxists in the Face of Fascism: Writings by Marxists on Fascism from the Inter-War Period (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2019); David Renton, Fascism: History and Theory (London: Pluto Press, 2020). In the original edition, Dutt is only discussed in a dismissive footnote as exemplifying the Comintern’s “class-blind analysis”. Renton, Fascism: Theory and Practice (London: Pluto Press, 1999), 134. Dutt’s fealty to Stalin and the Communist International (Comintern) has largely consigned his works to obscurity, but charges by his detractors on the left that he was just an opportunistic “shyster lawyer” overlook his deep-seated commitment to anti-imperialist causes.

Empire, “the British form of fascism”

While conventional accounts stress the exceptional character of fascism, owing to national and cultural peculiarities, when contextualised within the long history of European colonialism, the horrors of the 1930s-40s appear less of an aberration. As the son of a Bengali immigrant residing in the metropolitan heart of darkness, Dutt viewed the great social turmoil of the interwar years through an anti-colonial lens – the “alien eye” as he called it – and as early as 1923 he argued that “the Empire is the British form of Fascism”.5John Callaghan, “The Heart of Darkness: Rajani Palme Dutt and the British Empire – A Profile”, Contemporary Record 5 no. 2 (1991): 257-75. He elaborated on this conviction in the book, which highlights how in the poems of Rudyard Kipling and the Boer War agitation of the Daily Mail, “the spirit of Fascism is already present in embryonic forms.” Dutt exposed the hypocrisy of the “democratic” imperialists, noting that “bourgeois critics of Fascism in Western Europe and America express their shocked indignation as if Fascist Germany and Fascist Italy were the first and only countries to go in for jingoism, wholesale war-incitement and war-preparation, and as if England, France and the United States were innocent angels of peace”.6Dutt, Fascism and Social Revolution, 182; 213. In the British Empire, the 1930s was a decade that witnessed the suppression of anti-colonial labour rebellions in the Caribbean, and the crushing of the Indian independence movement.

Having experienced imperial racism first-hand in England, Dutt identified that fascism’s “national-chauvinist ideology, the anti-Semitism and the racial theories are all borrowed, without a single new feature, from the stock in trade of the old Conservative and reactionary parties”.7Ibid., 183; Callaghan, Rajani Palme Dutt, 10. He pointed out that Britain’s home-grown fascists led by Oswald Mosley took their inspiration from not only Mussolini’s Black Shirts but also the perpetrators of the Amritsar massacre in India, and the paramilitary Black-and-Tans in Ireland. The American ruling class was “equally adapted to Fascism”, having “had plenty of experience in their own domain in the suppression of the twelve million Negroes within the United States and of the heavily exploited immigrant populations”. Dutt singled out the Scottsboro trial, Red-baiting, Haymarket hangings and Ku Klux Klan lynchings as examples of “the plentiful basis for Fascism in American bourgeois traditions”.8Dutt, Fascism and Social Revolution, 238-41. The centrality of imperial politics to British fascism has only recently been acknowledged by historians. See Liam J. Liburd, “Beyond the Pale: Whiteness, Masculinity and Empire in the British Union of Fascists, 1932-1940”, Fascism: Journal of Comparative Fascist Studies 7 no. 2 (2018): 275-96. The Nazi race laws indeed drew directly on the precedents of Jim Crow, as well as the genocide of Native Americans.

A parallel analysis was advanced by the Trinidad-born communist George Padmore (a regular contributor to Dutt’s Labour Monthly), who wrote after Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 that slaughtered 275,000 Africans, that “the Colonies are the breeding ground for the type of fascist mentality which is being let loose in Europe today”.9George Padmore, How Britain Rules Africa (New York: Negro Universities Press, 1969), 4. This interpretation was most famously advanced in Aimé Césaire’s 1950 Discourse on Colonialism, which argued that Hitler’s real crime in the eyes of “civilised” Europeans was “that he applied to Europe colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved exclusively for the Arabs of Algeria, the ‘coolies’ of India, and the ‘n****s’ of Africa”. Years earlier, Dutt had already suggested that Nazism was the rogue child of conventional European imperialism: “If Hitler applied the match to the gunpowder, it was the British and French ruling class that laid the trail of gunpowder and placed the match in his hand”.10Quoted in Neil Redfern, Class or Nation? Communists, Imperialism and Two World Wars (London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2005), 101. Hitler referred to his hoped-for German Lebensraum in Russia as “our India”, and the Nazis learned from previous colonial atrocities such as the Herero and Nama genocide in Namibia.11Renton, Fascism: History and Theory, 16.

Colonial rivalry and hungry imperialists

The book also cuts through Britain’s patriotic mythos of WW2 as a straightforwardly anti-fascist war fought in the name of democracy. At the time Dutt was writing, it was “the widespread hope of imperialist circles, especially in Britain, to use a re-armed Fascist Germany, in unity with Japan, for war on the Soviet Union”.12Dutt, Fascism and Social Revolution, 217. So long as the Nazis faced eastwards they were financed by the British ruling class, which backed Hitler’s rearmament programme in the Anglo-German naval agreement. Former Liberal Prime Minister David Lloyd George described Hitler as a bulwark against Bolshevism, while Churchill declared that if he were Italian he would “wholeheartedly” support Mussolini’s counterrevolution.

Unlike the more influential Marxist theorists of fascism including Georgi Dimitrov and Leon Trotsky, Dutt situated its rise in the crucible of inter-imperialist rivalry for colonial markets in the context of a global economic crisis like that which preceded WW1. The arrival of fascism, Dutt argued, can “only be correctly understood in relation to its general social role as the expression of the extreme stage of imperialism in break-up”. The divergent national trajectories were principally accounted for by the fact that while Britain and France were “sated” colonial powers “gorged with world-plunder,” Germany, Italy and Japan were “hungry” imperialists “intent on an aggressive policy of expansion”.13Ibid., 213-16. A similar conclusion was drawn by the German left-social democrat Richard Löwenthal, who identified the essence of fascism in “an imperialism of paupers and bankrupts”.14Richard Löwenthal, “The Fascist State and Monopoly Capitalism” (1935), in Beetham ed., 339. Mussolini himself described Italy as a “proletarian nation” in Europe unjustly denied its share of colonial possessions.15Renton, Fascism: History and Theory, 13.

In a misfortune of history, Dutt’s farsighted anti-imperialist analysis was marginalised only months after the book was published – when the Soviet Union turned towards courting alliances with the “democratic” Allied powers – and downplayed its previous anti-colonial commitments. Dutt resorted to ideological contortions to justify the Comintern’s volte-face, but the notion he was merely “Stalin’s mouthpiece” in Britain is simplistic. For instance, during the “People’s War” phase after the German invasion of Russia he argued – in contradiction to the Soviets’ conciliatory approach – that support for Britain’s anti-fascist war effort should be “combined with continued struggle against Churchill and British imperialism”.16Callaghan, Rajani Palme Dutt, 198.

Dutt’s insights have sustained relevance in our present era of far-right resurgence and renewed antagonisms between the “core” capitalist powers with a principle difference being that today, there are only hungry imperialists. While contemporary incarnations of fascism require special attention, the danger of exceptionalism remains: as Joshua Briond reminds us in his article titled “Hitler Is Not Dead” (a nod to Césaire), the mass incarceration and deportation of migrants, anti-black police brutality and imperialist wars in West Asia “occurred long before Trump and will continue to escalate long after Trump”.

From social imperialism to “social fascism”

Dutt also analysed the internal “fascisation” of bourgeois democracy. Following Lenin’s framework of “the law of unequal capitalist development”, he noted that social contradictions were sharpest in the “poorer” imperialist countries, where the ruling classes were no longer able to purchase social peace, and thus had to rely on increasingly authoritarian measures to keep workers at heel.17Dutt, Fascism and Social Revolution, 216. Dutt was off the mark in arguing that the entire capitalist world was entering a state of “pre-fascism”, but his apocalyptic tone can be excused given the circumstances – few living through the calamity of the thirties could have anticipated capitalism’s post-war recovery.

The book presents the most systematic defence of the controversial “social fascism” thesis, showing how social democratic parties helped pave the way for fascism through implementing emergency powers, refusing anti-fascist alliances with communists, and forestalling proletarian revolution. The social fascist position was promoted by the Comintern during its Third Period (1928-34) when it designated reformist politicians as class enemies. Dutt glossed over the undoubted sectarian excesses of this policy, but those who write it off as “ultra-left idiocy” too readily forget the line was solidified only after a series of fatal betrayals by governing social democrats, climaxing in the 1929 shooting of May Day demonstrators in Berlin.18Ibid., 116.

Whereas Trotskyist accounts tend to overstress the middle class base of fascism, Dutt correctly saw that it was able to mobilise and deceive swathes of the “demoralised working class” disaffected from social democracy. This dynamic enabled fascism to become a truly mass movement with the capacity for self-radicalisation, distinguishing it from previous “dictatorships from the right”.19Ibid., 82; 76. To his credit, Renton also acknowledges this dynamic: “Even if the petty bourgeoisie played a disproportionate role in fascist parties, it was such a small minority in society that it could not be the source of every single fascist … Part of the horror of fascism was that it recruited people who could easily have been won over by Socialist parties.” Fascism: History and Theory, 153. The purported “twinned” character of fascism and social reformism was more sophisticated than is often implied: the argument was not, as Renton suggests, “that social democracy was just another kind of fascism”.20Renton, Fascism: History and Theory, 79. Both are in the last instance “instruments of the rule of monopoly capital”, both attempt to place “the state above classes”, but their methods differ. Where fascism “shatters the class organisations of the workers from without”, social democracy “undermines [them] from within”. For Dutt, what was novel in the fascist dictatorship was that rather than incorporating the existing labour movement into the imperialist state, it aimed at “the violent destruction of the workers’ independent organisations”.21Original emphasis. Dutt, Fascism and Social Revolution, 115; 203.

More originally, the book argues that fascism was specifically indebted to a western socialism that had betrayed class internationalism, and “left the masses an easy prey” to far-right demagogy.22Ibid., 162. Dutt recognised that European social democracy itself had “been built on the foundation of colonial slavery; as was strikingly demonstrated when the Labour Government, the champion of ‘democracy’, brought in a reign of terror to maintain despotism in India and jailed sixty thousand for the crime of asking for democratic rights”. The fascist conception of imperial “self-sufficiency” was a familiar one among the reformist left in the 1930s. Dutt noted that when the Labour MP and future fascist Oswald Mosley advanced his programme for national economic growth based on “socialistic imperialism”, prominent left-Labour politicians, including Aneurin Bevan (the later architect of the National Health Service), “rallied to his support and assisted his campaign.”23Ibid., 235; 255.

Like many communists, Dutt had been radicalised when the reformist parties of the Second International succumbed to the jingoist frenzy and backed their respective governments in the imperialist First World War. He observed that the ultra-nationalist rhetoric of “war-socialists” such as Robert Blatchford in England and Alexander Parvus in Germany “reveal many striking resemblances with subsequent Fascism”.24Ibid., 157. In Italy, a number of prominent fascists including Paolo Orano were erstwhile revolutionary syndicalists, who saw their country’s participation in WW1 as a moment of national redemption.25Zak Cope, The Wealth of (Some) Nations: Imperialism and the Mechanics of Value Transfer (London: Pluto Press, 2019), 180. The early pseudo-socialism of Nazism, as articulated by the Strasser brothers, also borrowed from the “semi-Fascist conceptions of nationalism, imperialism and class-collaboration”, which were long fostered by the chauvinist wing of social democracy.26Dutt, Fascism and Social Revolution, 162.

Within the western left of today, a reinvigorated class politics remains stuck in the social-imperialist cul-de-sac. Emblematically, in 2018 the prominent journalist Paul Mason – soon to publish a book on “how to stop fascism” – called for Jeremy Corbyn to advance “a programme to deliver growth and prosperity in Wigan, Newport and Kirkcaldy – if necessary, at the price of not delivering them to Shenzhen, Bombay and Dubai”. By pandering to nativism and anti-immigrant sentiments, social democratic and liberal parties throughout Europe and North America have continued to play into the hands of right-wing populism. Dutt should be recognised alongside the likes of Padmore, Sylvia Pankhurst, and Amílcar Cabral for demonstrating that the only effective counter to creeping fascisation lies in the path of anti-imperialism and socialist internationalism.

Alfie Hancox writes about anti-imperialism and intersectional working-class movements in Britain. He is currently researching the history of British Black Power.