Robbie McVeigh and Bill Rolston’s ‘Anois ar theacht an tSamhraidh’ Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution is one of the finest works of Irish and anti-imperialist historiography written to date.1‘Anois ar theacht an tSamhraidh’ a line from the traditional Irish song, Óró sé do bheatha abhaile, translates as ‘Now that summer’s coming’. Published in June 2021 by Beyond the Pale books, it fills an enormous gap in Irish political discourse, which has tended to overlook the influence of imperialism on the particularities of Irish capitalism. McVeigh and Rolston frame these issues within a longue-durée perspective, reaching as far back into the past as ancient Celtic society and as far forward as the COVID-19 pandemic. Their scholarly apparatus is hugely impressive and McVeigh and Rolston offer an enormous number of examples drawn from world history. Despite this, the book has not received the attention it deserves and has not yet been reviewed in any major publication. What follows intends to rectify this state of affairs.

McVeigh and Rolston position their work as emerging from a post-2008 moment, a point at which the global capitalist system was brought to the brink of collapse as the extent of the fictitiousness of global bank balance sheets and property investment portfolios became clear. Out of this came the collapse of the twenty-six county state’s ‘Celtic Tiger’ economy, the discrediting of an economic model that provides special tax arrangements for multinationals to secure investment, the collapse of the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) and the United Kingdom leaving the European Union.2The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 imposed a border on the island of Ireland, separating six counties in the island’s north-eastern corner — Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone — from the other twenty-six counties. This was undertaken in order to secure British imperialism on the island as well as to bolster the unionist dispensation within this synthetic construction. As this border violates the terms of the Irish Republic, declared as an all-Ireland state in 1916, the titles one uses in order to refer to either of these entities are highly politicised as they ascribe legitimacy, either to the Republic locating itself in a broader history of anti-imperialist struggle, or the border imposed on the island which overturned the will of the Irish people, as expressed in the election of 1918. A Fine Gael-Labour coalition government declared the twenty-six county state to be the Republic of Ireland in 1949, but for many Republicans this affords a legitimacy to the idea that two separate states exist on the island and that the Republic possesses no territorial claims on the six counties. For those who accept the legitimacy of partition, the six-county state in the north is referred to as ‘Northern Ireland’, while Republicans opt for ‘the six counties’, ‘the northern statelet’ or ‘the occupied territories’. While those who accept the legitimacy of the twenty-six county state would refer to it as ‘The Republic of Ireland’ or ‘the Republic’, Republicans would refer to it as ‘the twenty-six counties’, ‘the south’ or ‘The Free State’. For the purposes of this review I use the terms ‘the twenty-six counties’ and ‘the six counties’. All these events have taken place in and around the one hundred year anniversary of a protracted period of social struggle in Ireland and have underlined the long-standing legacies of imperialism and placed new emphasis on the importance of self-determination.

McVeigh and Rolston demonstrate how resources from Ireland’s past can inform developments currently underway in radical politics. More traditional models of industrial worker power in the west, expressed in mass action or general strikes, have come under severe pressure over the past half-century, through bureaucratisation as well as more direct attacks on trade unions, casualisation of labour contracts, containerisation and de-industrialisation. As such, working-class unrest increasingly expresses itself more spontaneously and among sections of the working class often referred to as forming part of the systematically under-employed ‘reserve army of labour,’; we might think of the 2011 London riots or the 2014 Ferguson uprising in this context. Through counter-insurgency consisting of armed operations undertaken by state forces and media co-option, the concessions the capitalist state metes out in response to these challenges are often highly regressive. Despite the electoral endorsement given to women’s reproductive rights in a 2018 referendum, reproductive rights in the twenty-six counties remain in many respects conditional. In answer to demands for specific police units to be disbanded in the US, additional funding is provided. Calls for reparations for the victims of the British Empire are used by the ruling class to stoke culture wars, which are themselves largely veneers for criminalising opposition, as can be seen in the content of the Conservative party’s Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Bill.

That McVeigh and Rolston are mindful of these developments is obvious. They make the effort to touch upon topics that have inflamed enormous amounts of online debate in recent years, such as Irish slavery, as well as the degree to which the Irish people have a case to answer as foot-soldiers of the Empire. The idea that the Irish have not been victims of Empire has developed currency firstly among well-intentioned people seeking to challenge cynical fascist usage of indentured servitude,3McVeigh and Rolston, Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution, 69. and secondly among anti-Republican revisionist historians, who have received ample space to spread their apologia for genocide in Irish newspapers. One of the many statistics McVeigh and Rolston draw our attention to are mortality rates for indigenous children separated from their parents and installed in residential schools in the Americas, which matched or exceeded those of the Nazi concentration camps.4McVeigh and Rolston, Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution, 51. Mass murder has therefore always been a crucial part of colonialism, which is why attempts to rehabilitate British, French, Dutch or Belgian imperialism, are undertaken only by the most reactionary blocs of the ruling class. McVeigh and Rolston however, shift the emphasis to historical actuality; the ambivalences as well as the very real solidarities that existed between the Irish and other colonised peoples, taking us from the idea that anti-imperialist politics should involve ascribing the correct amount of guilt to both sides.

McVeigh and Rolston divide the history of imperialism into stages. The first was initiated by Spain and Portugal who divided the world in the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, making large territorial acquisitions and vassals of the peoples they encountered. With the emergence of the Dutch Empire more recognisably modern economic relations can be identified, with private commercial concerns, shipping routes and mercantilism. The Dutch East India Company established the first capital market, opening the benefits of imperialism to a broader stratum of society beyond the aristocracy. France and England then launched similar ventures and furthermore imposed restrictions to prevent their settlements from trading with any other country; thereby become enormously wealthy. In the nineteenth century, the European powers divided Africa and Asia until ‘by the start of World War I, nearly all the world outside Europe… had been formally colonised at some point by at least one European state’.

As Vladimir Lenin argued, World War I was a natural outgrowth of the world the imperial powers had created. With no markets left to expand into, they had no choice but to turn against themselves. The old European colonial system entered into terminal decline from the end of World War II, but not without having shaped the new global order. Large parts of the globe had been systematically underdeveloped, meaning that strict limits were imposed on decolonisation as an economic as well as a political project. The failure or inability of South Africa’s ANC to transfer back to its original owners as it set out to do is just one of many examples. Sections considering this history are excellent, dense with information about the concrete operation of colonialism, the selective apportioning of voting rights, citizenship being denied indigenous peoples and racial hierarchies within the supposedly independent states. 5McVeigh and Rolston, Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution, 314-26.

McVeigh and Rolston also demonstrate that Ireland has not in any sense been decolonised and that imperialism has shaped the structure of the two statelets on the island. McVeigh and Rolston argue this has been an oversight in the works of the canonical theorists of the state, such as Jürgen Habermas, Michel Foucault, Ralph Miliband and Nicos Poulantzas. These theorists have all, to greater or lesser extents, developed abstract models of nation states in the imperial core, which are not subject to the same dynamics of underdevelopment, unequal exchange or militarisation of state forces that prevail in former and current, colonies. Our understanding of the social dynamics surrounding class, religion, and gender in an Irish context would therefore all be very poorly served by adopting these theories uncritically.

What is widely understood to be the first moment in the Irish state’s inception was the declaration of the Republic declared in Easter 1916 and ratified by the Irish people in an election in 1918. This was the first and only stage in Irish history in which we have seen the will of the Irish people express itself in an election, with the exception of younger women who were not afforded the franchise. The Irish people’s struggle to extricate themselves from Empire; British, American or European, remains ongoing. It would not be uncommon for individuals or organisations on the Irish left to ridicule the invocation of the Republic in the present moment. The Official IRA / Worker’s Party often wrote off Republican struggle as the expression of lumpen elements within the working class, often valuing their connections with loyalist paramilitaries armed and assisted by British Intelligence, such as the Ulster Volunteer Force and the Ulster Defence Association, over and above the nationalist working class. McVeigh and Rolston demonstrate that since the forced exile of the Celtic aristocracy, the struggle for national self-determination has by necessity fallen to the Irish peasantry and the most immiserated sections of the working class. Furthermore, ‘a state built on inequality finds the demand for equality metaphysically threatening… the demand often has side effects long before the ultimate point is reached’. A full inquiry into the psychology of the ruling class in the twenty-six county state is too broad a subject for the purposes of this review, but the palpable discomfort the political establishment exhibit around the decade of centenaries, the eagerness with which they have proposed initiatives such as a state celebration of colonial police, joining a monarchical trading bloc or guaranteeing cabinet seats to unionists, will serve well enough for our purposes for the moment.

Descendants of the original Norman colonists of the twelfth century largely assimilated into the Irish population, began to speak Irish, marry Irish people and take on Irish customs.6McVeigh and Rolston, Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution, 67-70. The colonisation of Ireland proper began with Poynings’ Law in 1494, which gave the English Crown claims on the Irish Kingdom. This was consolidated with the Plantations of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, during which English planters were granted lands in southern and eastern parts of the country. These ventures initially failed, both due to administrative incompetence as well as native resistance. Discontent reached a climax with the 1641 uprising, which prompted Oliver Cromwell, the Lord Protector of the newly-declared English Republic, to invade and crush the nascent Irish Confederate government. That this Confederacy was more progressive than it is often given credit for and planned to institute measures of religious toleration, has not received nearly enough attention in the historical discourse, which tends to uncritically repeat British propaganda framing 1641 as a sectarian eruption of Catholic barbarism in which thousands of Protestants were massacred in uniquely brutal and inhumane ways. Cromwell granted poor-quality land to Catholics who could demonstrate they had no part in the rebellion in western parts of the country and many prisoners were sent as settlers or workers to the Americas and the Caribbean.

English identity proper begins with these exercises in subjugation and the clear distinction which arises between the conquerors and the conquered. The Irish are held to be idle, lazy and uncivilised Catholics versus the industrious and civilised Protestant English. This idea of England and a racialised conception of Englishness wields immense ideological power throughout the history of the British Empire, but was never concretised in any state formation outside of it; rather it is merely not-Wales and not-Scotland. In order for the plantations to remain viable it was necessary that Irish resistance be crushed. Massacres, forced deportations and clearances were undertaken as a first step and then a system of apartheid was enforced. Land grants became conditional on restricting the number of servants or tenants drawn from the native population. Vivid descriptions of the human cost and aftermath documented by perpetrators, victims and onlookers abound and it is easy to see echoes of Christoper Columbus’ butchery in the Americas.7McVeigh and Rolston, Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution, 294-95. The British response to each instance of native resistance became an opportunity for imposing draconian legislation. The Penal Laws, introduced towards the end of the seventeenth century prevented Catholics from obtaining positions in the state bureaucracy, the professions or the judiciary. They could not handle firearms, intermarriages were outlawed and any orphan had to be parented by a Protestant.

Ireland’s containment within the 1801 Act of Union, afforded some expansion of the vote to Irish men who owned or rented property worth more than 40 shillings. This measure was never granted to peoples in England’s other colonies and led to figures within the Irish middle-class seeing the opportunity to receive some share of the Empire’s dividends. It is within this tradition that figures such as Daniel O’Connell, Isaac Butt and Arthur Griffith, each of whom were involved in various parliamentary ventures through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, are best understood. To the extent that the Irish were admitted into Empire, they were definitively junior partners; both due to its unpopularity — merchants in Belfast and Galway seeking to establish slave-trading companies are documented as having had their meeting interrupted by the future United Irishman Thomas McCabe who declared ‘May God eternally damn the soul of the man who subscribes the first guinea’ — as well as the British seeking to maintain their monopolies. British manufacturers succeeded in ending the woollen trade and ensuring the Irish peasantry could not diversify their agriculture, leaving them uniquely vulnerable to the catastrophe of An Gorta Mór, during which Irish grain was continually exported to feed the British working class.8An Gorta Mór, or in English, ’The Great Hunger’ is the term used by Irish Republicans and socialists in order to underline the role of British imperialism in the event and not a mere consequence of a blight on the potato crop. There are of course a surfeit of examples of individual Irish people who entered into armed service on the Empire’s behalf and were involved in subduing native peoples in Africa, Asia and the Americas, even if we might feel as though figures such as Michael O’Dwyer are over-represented by The Irish Times as if they represented some sort of norm. It is important to recall as well that Irish Catholics were foot-soldiers and that their officers were drawn from the ranks of the English and Anglo-Irish.

McVeigh and Rolston square this circle through the idea of dominion, the ways in which the limitations of post-colonial statehood have been radically proscribed by imperialist powers. One of the most striking examples is the inability these supposedly post-colonial states have to rid themselves of borders drawn up by the imperialists, due to imperial self-interest or on the basis of arbitrary distinctions between racial, ethnic or religious groups. Democracy therefore becomes a gift the imperial state bestows upon their subjects, retrospectively casting all historic resistance as illegitimate. The British partition of Ireland in 1922 can be understood in this context. The six-county statelet did not align with the historic province of Ulster.

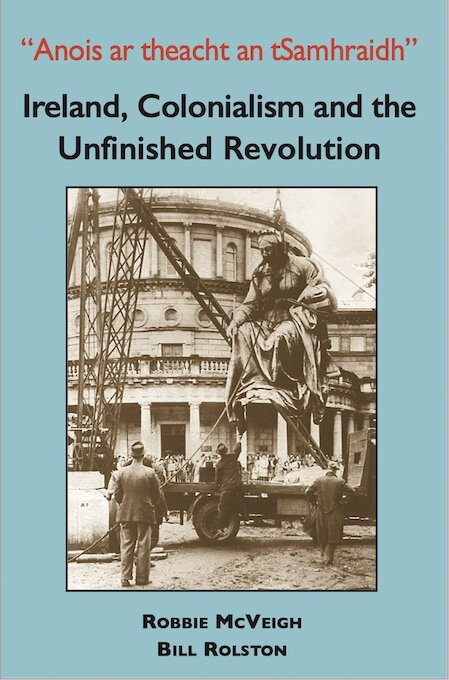

Many will already be familiar with the central argument of Noel Ignatiev’s How the Irish Became White (1995) in which it is argued that Irish labourers sought to assimilate themselves with the interests of the white and Anglo-Saxon Protestant establishment in the US rather than making common cause with freed slaves and their descendants. From McVeigh and Rolston’s perspective, Ireland did not become the anti-imperialist and revolutionary state on which the Republic was declared because of partition. The Anglo-Irish Treaty merely tinkered with some aspects of the relationship of the Irish nation to Empire; both statelets remained within it. This can be seen by the power the British continued to wield over the twenty-six counties; the Irish currency was linked with the British sterling until 1978, the British considered the twenty-six county state a member of the British commonwealth until 1949 and representatives even attended imperial conferences in London. The Free State also continued to compensate British landlords who had acquired their lands through colonisation. When Republicans opposed to the Treaty established a garrison in the Four Courts in Dublin, a building in which Ireland’s higher courts have been housed since the eighteenth century, British Prime Minister Lloyd George ordered the Minister for Finance in the Free State government Michael Collins, to engage them and Winston Churchill even planned to do so himself. The Republicans were unable to secure a foothold in the cities and therefore retreated into the countryside to wage guerrilla warfare. W.T. Cosgrave, Chairman of the Free State Government after Collins was assassinated by Republicans in West Cork, passed a ‘public safety bill’ which empowered the armed forces of the Free State government to execute Republican combatants. In this way the twenty-six county state comes into existence, as Karl Marx described the birth of capitalism, ‘dripping from head to toe, from every pore, with blood and dirt’.

Fianna Fáil, elements of the Republican movement which accommodated themselves to the Free State became its natural party of government and only symbolically committed themselves to re-unification as a long-term goal. Despite rhetoric from more populist figures in Fianna Fáil, the twenty-six county state never defended the Catholic population from British forces, was always eager to shed Irish claims on territory and never sought to hold the British state responsible for the murder of its own citizens in the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, the worst atrocities committed in the whole of the Troubles. After a brief period spent pursuing economic and political autarky, the state began to pursue an economic model based on securing investment from overseas and joining the European Economic Community (EEC). Charles De Gaulle vetoed the twenty-six county state’s entry, regarding the twenty-six counties as a vassal of the UK. Sure enough, the Free State government did not regard entering the trading bloc independent of the UK as a viable option. In this way accession to the EEC further solidified the twenty-six county state’s neo-colonial status.

The democratic deficits that have followed will be familiar to anyone who has looked into the EU’s peripheries; the effective abrogation of sovereignty and an increasing tendency towards militarisation and so-called peacekeeping activities overseas. While McVeigh and Rolston emphasise that whatever dividends can be ascribed to the twenty-six county state’s tax haven status amount to state propaganda, these initiatives frequently enter into contradiction with EU membership. Without it, McVeigh and Rolston speculate, the twenty-six county state would probably look more like the Isle of Man or the Virgin Islands.

Once the economy of the twenty-six county state entered into a protracted boom period from 1995 until 2007, it experienced significant amounts of inward migration for the first time in its history. This prompted the imposition of new regulations of the Free State’s labour markets, and the emergence of a new blood-and-soil rhetoric around twenty-six county nationality. McVeigh and Rolston identify this as a turning point, indicating that the conditions which formerly existed for the extension of Irish identity to people of colour no longer exist and are unlikely to re-emerge as Ireland remains within the EU/UK dominion.

During the War of Independence the IRA in the northern parts of the country faced a very different prospect than in the south. State forces waged far more determined armed resistance and more extensive pogroms and assassinations of Catholic civilians. Sectarianism was encoded into the very structure of the six-county statelet that arose out of partition which McVeigh and Rolston convincingly describe as a proto-fascist Herrenvolk democracy.9McVeigh and Rolston, Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution, 212. Native capitalists who were also often ministers in the partitionist parliament would only hire Protestant workers. All-Ireland campaigns for the liberation of the north were largely desultory. Northern Protestants were successfully recruited in the early stages of The Republican Congress’ campaign, although these elements left after a confrontation with IRA members at a commemoration in Bodenstown. This state proved in the long-term to be non-viable. Indigenous industries were bought out by foreign capital after the global slump in the 1930s and heads of industry became mere intermediaries. The social actors foregrounded in other accounts of the Troubles at this stage in the work recede in favour of a focus on economic relations, capital ownership and differences in employment figures across the Catholic and Protestant population.

McVeigh and Rolston are unstinting in their criticism of the six-county state that has emerged in the wake of the GFA, seeing it as yet another example of a failed instance to fully escape imperialist dominion by enlisting a broader set of political parties north and south of the border in order to prop up a failed economic and political entity. The GFA was not, as John Hume sought to argue, an instance of self-determination by the Irish people. The votes were not aggregated and it therefore remained firmly within the two nations paradigm. The essential basis of the agreement was that Republicans would stop using violence against the statelet so sectarianism and clientelism could be dismantled. This winding up of the excesses of the wartime security regime, which employed 10% of Protestant men, as well as de-industrialisation has led to a state of affairs in which the twenty-six county state has an economy four times larger with a workforce only 2.5 times the size. Sectarianism has not been broken with, but rather encoded into the ‘reformed state’ such that the increasing migrant population have limited space for political representation, despite representing 10% more of the working population than Protestants. Community funding are apportioned within areas in which particular political parties have a larger vote share and the latent genocidal tendencies in the unionist community are pandered to. Post-2008 these issues have only come into sharper focus; the six counties cannot offer Protestant supremacy, but nor can it provide parity to the Catholic population, who remain more likely to be long-term unemployed. 158 political killings have occurred since the agreement was passed and state forces remain complicit in killing of Catholic civilians.

The final sections of the book consider the history of the broader anti-imperialist movement, outlining how the UK, the US and Israel have successfully put the breaks on decolonisation by exercising their vetoes in the United Nations, as well as imposed sanctions, blockades or conducting assassinations of prominent leaders. The footnote in which the death toll we can lay at the feet of the CIA, Mossad as well as various British and French intelligence agencies is long, non-exhaustive and very depressing.

Despite the Free State’s incorporation within UK and EU dominion, there are moments in which the twenty-six county state, under consistent popular pressure, expressed support for Algerian, Chinese and Palestinian independence struggles. It is here that McVeigh and Rolston demonstrate the ways in which Irish history has always been a site of struggle between nationalism and Republicanism. While the Young Irelander John Mitchel, transported to Australia in 1848 for his agitation against landlords and the export of Irish grain to Britain may have been an apologist for slavery, at a mass meeting addressed by Charles Stewart Parnell held in Navan in 1879, 30,000 Irish people chanted the name of the Zulu king Cetshwayo, at that point waging a war of resistance against the British.10McVeigh and Rolston, Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution, 298. The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), a clandestine organisation founded in 1858 devoted to the establishment of the Irish Republic even attempted to send $20,000 and military strategists to assist the Zulus. Among the many colonised peoples who sought direct inspiration from the Irish independence struggle include Indian nationalists, freed slaves in the US and Marcus Garvey who named the headquarters of the UNIA in New York Liberty Hall in reference to James Connolly.

In assigning a central position to the history of struggle for self-determination in Ireland, McVeigh and Rolston demonstrate how intersectionality may be bolstered within an Irish context by having its demands relate themselves to calls for social equality which have historically been made by the Republican movement. This is to be undergirded by the concept of mestizaje, which acknowledges the hybrid nature of the colonial state and transcend categorisations which might otherwise function in sectarian ways. Though the progressive tendencies of, for example, the Republic declared in 1867 should not be forgotten, the rebellion organised by the United Irishmen in 1798 is of course the key example and deserves to be understood, along with the Haitian Revolution, as among the first modern anti-colonial uprisings, inspired by the universal politics of the French Revolution but moving beyond self-determination for colonists to a radical vision of postcolonial self-determination.

It is only towards the end of the work that McVeigh and Rolston discuss political strategy directly. In many respects their programme is significantly more radical than one would expect from a scholarly work; McVeigh and Rolston argue that we are living in a revolutionary moment in which the Union, the British state and the six counties are in a state of collapse. Though this may be the case, their claim that this current state of affairs offer a clear ‘’reformist’ route to liberation’ requires further interrogation.11McVeigh and Rolston, Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution, 402.The model that McVeigh and Rolston cite, is that of the Parnellite popular front of the 1880s, when Charles Stewart Parnell led the Irish Parliamentary Party bringing together ‘insurrectionary movements, mass mobilisations and representative parliamentary intervention’. What exactly is meant by ‘insurrectionary movements’ is hedged here. McVeigh and Rolston posit that the ‘the republican movement ditched insurrection as a core principle’ which would obviously preclude ‘dissident’ Republican groups from being considered, although the word ‘dissident’ is also put in quotation marks. This is probably the most pragmatic line to take, I do not see the sense in being proscriptive as to what the revolution will look like.

McVeigh and Rolston’s idea that this moment opens up ‘a whole new continuum of broader Republican thinking from Fintan O’Toole to the politics of the “dissidents”’12McVeigh and Rolston, Ireland, Colonialism and the Unfinished Revolution, 405. is generous, given O’Toole has had a lifetime to do more than pay lip service to what he calls ‘classical Republicanism,’ a term that can only be interpreted as anything other than actually-existing Republicanism, and has not done so. Dan Finn’s survey of O’Toole’s career underlines that he is a model of a vacillating intellectual, whose default position is to cosy up to the Labour Party, whose historic function is and will continue to be to betray the working class and to provide Fine Gael with a working majority. This is all without getting into his post-Brexit output, the only word for which is ‘embarrassing’. Marriage equality and Repeal certainly offer encouraging signs of a mass base for a socialist and anti-imperialist movement, as younger and more working class elements in the population circle Sinn Féin as a likely parliamentary vehicle for the delivery of some approximation of social democracy. This has already led Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael to advocate unionist positions due to the electoral calculus of a United Ireland. I do not think a revolution in Ireland backed by the EU or partitionist parliaments is likely to be democratic, nor do I think the counter-revolutionary tendencies of a decaying Union should be understated.

Had this excellent book been longer it might also have provided McVeigh and Rolston space to consider in greater depth where we are now and where we have to get to. What lessons can anti-imperialist movements of the future take from the previous century? What are the prospects for organising worker power? In what way do we need to adjust the classic model of industrial worker organising in the context of low-wage service economies? It would be possible to argue that providing conclusive answers to these questions are a matter of practice and we should not expect conclusive answers to them within the confines of a single work. And so we should not. A political discourse that would take this work as a starting point would be a far better one than the one we have now and in overall terms, these small oversights should not distract from the central point; McVeigh and Rolston must be applauded for the contribution they have made in bringing one of the greatest works that has ever been written on the subject of imperialism into the world and everyone should read it.

Chris Beausang was born, and continues to live, in Dublin. His novel Tunnel of Toads is forthcoming from Marrowbone Books.