Basel did not call on us to be resistance fighters. Nor did he call on us to be revolutionaries. Basel told us to be true, that is all. If you are true, you will be revolutionaries and resistance fighters.

Khaled Oudatallah in a eulogy for Basel al-Araj in al-Walajah, March 8 20171Basel al-Araj, I Have Found My Answers, (Bisan, 2018), 388.

It couldn’t have been more than a few weeks after I had started a new role with a refugee rights organization in Bethlehem. It was the end of a workday when a friend and colleague, said to me “I have a cousin who is interested in political things like you. You should meet him… come, he’s expecting us.” Into his car we went, up the hill through Beit Jala and past the Israeli military base and checkpoint known as the “DCO” and into the village of al-Walajah. We drove to what looked like a residential home, but when we entered I realized it had been transformed into a youth center. Standing behind a desk in the middle of the entrance room was a thin man with thick glasses, somewhere in his mid-twenties. His name was Basel al-Araj.

Unlike most interactions between people meeting for the first time, this one involved almost no pleasantries. Somehow, both Basel and I realized that we could skip them, and that we preferred it that way. Within minutes he was talking me through the various maps and documents he’d prepared for my visit. An engaging story-teller, he was one of those people who are masters of communication, but for whom language felt like a curse – so much knowledge to share, so many stories, but you can only say one word at a time. Despite this, within what felt like no time at all, and illustrating each point with a document, Basel had shown me that al-Walajah is a microcosm of the Palestinian struggle.

On the eve of the Nakba, al-Walajah had a population of around 2,000 Palestinians living on over 20,000 fertile acres, dotted with fresh springs throughout the hills on both sides of the valley. The village itself was on the hilltop to the west of the valley – the Valley of the Giants in the Old Testament – where the Jaffa-Jerusalem railway was built in the 1890s. In October 1948, Zionist forces expelled all of the village’s inhabitants, and took control of over 12,000 acres of the village’s land. Most of the displaced villagers crossed over to the other side of the valley to the eastern hill of the village that came under Jordanian control after the 1949 armistice agreements – the valley itself becoming part of the armistice (or “Green”) line between the West Bank and the new Zionist state.

The sun had begun to set in the middle of our conversation. Basel took me outside and pointed west. The colors were spectacular, but that wasn’t all he wanted me to see – just below the resplendent reds and oranges was the silhouette of a Zionist settlement; amidst the shadows were some buildings with the iconic old stone that immediately identifies Palestinian buildings built before 1948. For all these decades, Walajees have been refugees on their own land, unable to see a sunset without looking at the remnants of their own village – now an Israeli settlement called Aminadav (which ironically translates as “a generous people”) – their springs now waterholes along a network of hiking trails used by Israelis and tourists.

In 1967 Israel occupied the new site of al-Walajah, which had been a refugee camp in all but name since the Nakba. Soon thereafter, Israel’s illegal settler colonies Gilo and Har Gilo, and the roads servicing them, were built on land that included 2,000 acres of what remained of al-Walajah. In 1980, the Israeli Knesset formally annexed Jerusalem, expanding its municipal borders to include parts of the new village but without extending Jerusalem residency rights to any of the inhabitants. Since then, Israeli police have harassed Walajees in those parts of the village, in some cases arresting them while in their own homes for being in Jerusalem without a permit.

Things only got worse after the Oslo accords, when what remained of the village’s agricultural land was effectively annexed to Israel. Soon thereafter, the Jerusalem Biblical Zoo was relocated to parts of al-Walajah’s land, and construction began on the apartheid-annexation wall which now renders al-Walajah an enclave that is completely surrounded by settlements, walls and settler-only bypass roads, with effectively only one entrance in and out of the village. In the years before I met him, Basel and other villagers had banded together to try to pave the roads that kept them connected to Bethlehem, and the Israeli military would repeatedly destroy those roads and arrest the villagers who dared defy the transformation of al-Walajah into an open air prison. I visited the village every month or two after that, sometimes seeing Basel, but most often not. On every visit I would notice a subtle change – a road that had been paved now destroyed, the fence around Har Gilo settlement a few meters closer to the road, a house that once stood, now demolished.

Thanks to Basel, I met many of the community’s leaders, as well as many of the older generation who remembered the revolutionary 1930s and the expulsion in 1948. I was collecting oral histories and interviews for television and radio2One of the radio pieces produced with Basel’s help starts at minute 15:37 of: https://archive.org/details/nakba_2008-05-15_17h_201605/nakba_2008-05-15_11h.mp3 to tell the story of what I had started describing as the “ongoing Nakba”, which al-Walajah exemplifies. Basel knew every one of them intimately, but didn’t want to be interviewed himself. After 2008, Basel and I lost touch. He’d moved to the Shu’fat refugee camp in Jerusalem to take up his first real job as a pharmacist (he studied pharmacy in Egypt during the peak years of the Second Intifada).

As the years passed, Basel became increasingly involved in the resistance movement as a regular at martyrs’ funeral processions and political lectures. He began to translate his immense knowledge into writing, and around 2014 he joined the Popular University as an instructor to give classes on the resistance history of Palestine and design walking tours in which he’d take participants through the details of past resistance operations. He helped start the Bab el-Wad online magazine so he and others could share their historical research and political analysis and reconfigure the relationship of knowledge production to the liberation struggle.

In early April 2016, the Palestinian Authority (PA) police arrested Basel and two of his comrades outside of Ramallah, stating that the detention was to “protect” the young men from arrest by Israel. Three other arrests were later added to this group. The men were tortured, and Basel had to be given medical treatment often in the first few weeks of interrogation. Four months later, no charges were filed, and the six men went on hunger strike to demand their release, resulting in a public campaign calling for the PA to let them go, which it eventually did in early September. It has become routine for the PA to do Israel’s dirty work of torturing Palestinians to attempt to extract information, then releasing them, handing over what they could discover to the Israelis, then facilitating re-arrest by the Israelis themselves. So it came as no surprise when Israeli soldiers began hunting down the six men after their release. All were hunted down in this way, but Basel evaded capture for six months.

On Monday March 6, 2017, Palestinians woke up to the news. At dawn, a specialized tactical unit of Israel’s Border Police had attempted to raid the house in al-Bireh where Basel was hiding. After a two-hour gunfight, the unit fired two rockets into the apartment, killing Basel al-Araj.

A History of Colonialism, A History of Resistance

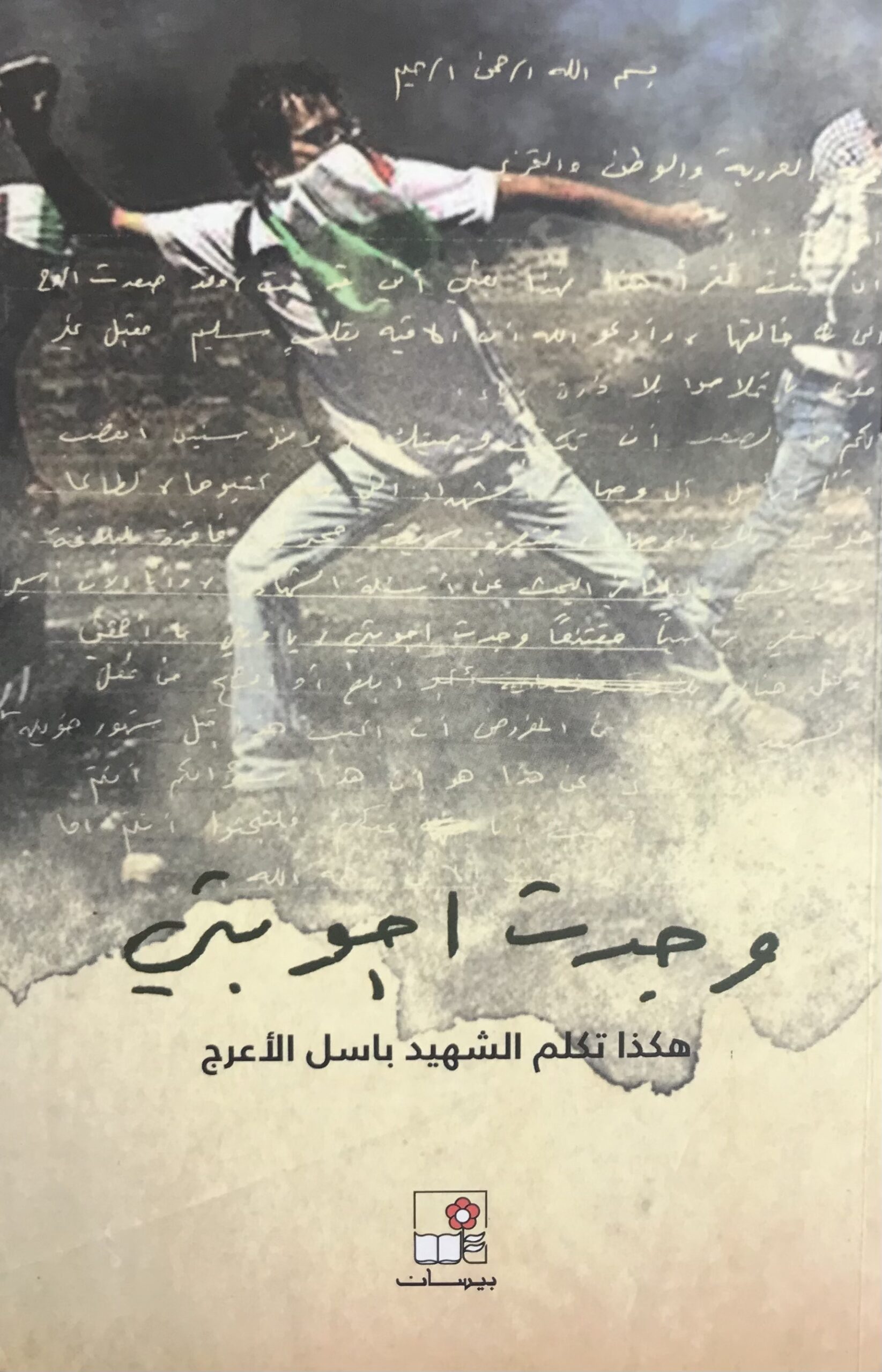

The Israelis held Basel’s body for eleven days before giving it to his family for burial in al-Walajah. Those who went into his hideout after the battle found a stack of his unpublished writings. A year after his martyrdom, Bissan bookshop (well-known to book lovers who have been to the Hamra neighborhood of Beirut) published a collation of these texts, together with some of his previously published work, as well as over one hundred pages of social media posts, and twelve obituaries and other texts written in remembrance of him, publishing them under the title I Have Found My Answers: Thus Spoke Basel Al-Araj.

The opening essay titled “The Wounded Memory of the Nakba”,3al-Araj, 17-34. begins with an abstract discussion of memory, but quickly becomes a retelling of the Nakba. It does not add much to existing histories of the Nakba empirically, but tackles it with an emphasis on the scale of the collective trauma, the use of massacres and rape; germ warfare, death marches and attacks on unarmed communities; lining villagers up against walls and shooting them down before getting their relatives to dig the mass unmarked graves they lie in to this day – all as means of terrorizing Palestinians. As with most of his other essays, Basel isn’t one for conclusions. Every essay leaves the reader to connect the introductory discussion with the nuts-and-bolts of the essay. In the case of his history of the Nakba, but unlike all the other essays, Basel’s emphasis is not on Palestinian heroism and the culture of resistance. It is a story of pain and the egregiousness of the crimes that the forced expulsions of 1947-1949 had entailed. Reading it, despite the ample footnotes to scholarly historical work, I can’t help but think of Basel hearing stories from his village elders, of the feeling of seeing their former homes silhouetted against every sunset. It is a reminder that the Nakba was a horror, lived in real time by our elders living and dead, not just a legal crime or a political event for which we seek redress. It is an exhortation to feel, over and above any invitation to think.

Among the only other pieces on the Nakba is also the only one where al-Walajah is at the center. But what sets “Gharba: Where I was born and where I will not Die”4al-Araj, 151-165.apart is that it is the only piece of historical fiction in the collection of essays. Here, Basel writes from the perspective of someone born into the al-Araj family in 1937. As the fruit of his many conversations with his family and elders, this piece is the story of the occupation, depopulation and destruction of al-Walajah in the Nakba. Almost every paragraph contains deep analysis of class, clan and gender disparities, and how they formed a backdrop to the forced removal of Palestinians from Palestine. It is an artful piece, mixing masterful standard Arabic prose, vernacular from the village, and even modified English words that had entered the lexicon.

One memorable example of Basel’s descriptive subtlety, for instance, is his description of the failure of neighbouring Arab states to provide a modicum of protection for Palestinians in the face of the Zionist military onslaught: “Two weeks later, some Egyptian forces entered the village to help with its defense. Most were regulars, some were volunteers. The volunteers fought with ferocity, the regulars ate all the chickens in the village.”5al-Araj, 159. This short story is a rich imagination of village life at the moment when it was clear that, as the story ends, “we’ve become refugees, and the country is gone”.6al-Araj, 165.

Later in the collection, his essay on “The Armed Struggle in the Revolution of 1936”7al-Araj, 77-84. is also empirical, but in a tone that characterizes most of Basel’s other writings; namely that Palestinian resistance history is one of immense and heroic accomplishment and a wellspring of lessons for the struggles ahead. He highlights the scale of the uprising, the thousands of operations, the high level of coordination and organization after August 1936 despite, and maybe because of, its decentralization, and systematically highlights the effectiveness of guerrilla warfare strategy in a situation of immense power asymmetry. He reminds us that “though it is largely a defensive strategy, its tactics are those of a war of attack” which enabled the revolutionaries to not only sabotage British occupation communications infrastructure, but to liberate and hold vast tracts of the country, including the cities of Nablus, Bir al-Sabe’ (Beersheva) and Jerusalem for months at a time in 1938.8al-Araj, 81.

Other essays include valuable historiographical interventions that relate to Palestinian resistance. In an article on the Black Hand group (“Al-Kaf al-Aswad”),9al-Araj, 47-52. a name made popular by the Serbian group that assassinated the Austrian crown prince in 1914, Basel begins by stating that he could find little well researched pieces of writing on this secret organization, and that what he found was often conflicting. Taking it upon himself to put one together, he finds that the main Black Hand group was a resistance organization that worked in secret in the 1930s, mostly focused on tracking and taking down Palestinians who collaborated with the British occupation, including spies and those facilitating land sales to Zionist organizations. The group was characterized by its horizontal organization, structured in such a way that no member knew any more than three or four others.10al-Araj, 47. Women were significantly active, especially in hiding weapons and in carrying out secure communications, including delivering ultimatums and demands. Basel then surveys other mentions of the Black Hand in Palestine (as well as Egypt, Libya and Syria), arguing that this was a name used by many different and unrelated groups from the 1920s until the mid-1950s. This effectively solves a particular source of historiographical confusion for histories of Palestinian resistance during the Mandate period.

Basel’s perspective on resistance history does not cast it only in the light of armed struggle, pitch battles and underground guerrilla cells. His essay on “Art in Palestine”11al-Araj, 85-101. resuscitates a mostly forgotten history of Palestinian cultural production in the mandate period that focuses primarily on poetry, song and theatre, with some mention of other fine arts. Though by no means comprehensive, the essay effectively points to a Palestinian cultural efflorescence, thoroughly tied to the broader region, and particularly Egypt from which many musicians and theatre troupes visited Palestine, and where many of the painters and sculptors studied at the then-recently established art academies.

His discussion of poetry and song provides in-depth discussions of many less renowned poets and popular singers The piece focuses on the role such figures played in marking historic events related to the struggle against British occupation and Zionist colonization as part of mass mobilization “using the poems as if they were militant communiqués and a means of spreading military knowledge and culture, a loud voice publicizing the strategies and orders of the leaders to the populace”.12al-Araj, 90. In a particularly memorable passage, Basel discusses the tactical use of songs, such as those women would sing outside prisons and in the hills where Palestinian commandos hid to deliver communications through coded language, and a version of the popular dal‘ona13A rural genre used when villagers would join together to help put up a roof to a fellow villager’s house. that would signal to the resistance that they were being used as human shields by British occupation troops and communicate their position.14al-Araj, 91.

Revolutionary Biography

The attentiveness to revolutionary biography, as is evident in his “Art in Palestine”, takes center stage in two other essays: “Abdelqadir Continues to Return to Jerusalem” (on Abdelqadir al-Husseini)15al-Araj, 102-118. and “Fawzi al-Qutb: For the Love of Gunpowder”16al-Araj, 127-136. in which Basel deepens his project of recoding well-known historical figures (al-Husseini is well established within the Palestinian pantheon of leaders and martyrs), and – as with the Black Hand group and the forgotten resistance singers and poets mentioned above – of shedding light on forgotten moments and figures whose stories are both instructive and deserving of membership in that pantheon.17Fawzi al-Qutb was a Damascus-born explosives expert who participated in the 1936 revolution, after which he was sent to Germany for further explosives training. When the Nazi army attempted to deploy him as a soldier, he refused saying “this is not my war,” (al-Araj, 131.) after which he was sent to the Wroclaw concentration camp, the tattoo from which he bore for the rest of his life. After the camp was liberated, he was detained by US forces, and upon his release he returned to Palestine and participated in the resistance in the 1948 Nakba.

He gives revolutionary biography particular attention as a genre in his essay “Out of the Law and into the Revolution”,18al-Araj, 137-143. which he introduces by reminding us that exceptional revolutionary figures are often cast either as bandits or heroes. After a foray into the literature on bandit-revolutionaries that brings together renowned pre-Islamic bandits in the Arabian peninsula, Frantz Fanon, Izz al-Din al-Qassam and Eric Hobsbawm, Basel settles on an analysis of the law as “a tool of normalized hegemony in the hands of authority,” which the state uses to give itself the monopoly on determining right and wrong. By doing so, it places both secret revolutionary organizations and the underworld of ‘criminality’ in the same “outlaw” status and incentivizing them to dig into the same pool of strategies and tactics to challenge power and evade capture.

With this introduction in place, Basel discusses a number of outlaws, starting with Ibrahim Hekimoğlu, an anti-feudal bandit from Ottoman folklore with a story almost identical (as Basel points out) to that of Robin Hood, William Wallace, and Henry Martini, the Iraqi revolutionary hero Suwaiheb al-Fallah (immortalized in the poetry of Muthaffar al-Nuwwab) and the Egyptian, Adham al-Sharqawi (the focal point of many a popular song). In all of these cases, Basel is attentive to how these symbols are then co-opted by state narratives to domesticate them for popular consumption, while attempting to derive legitimacy for state power through this co-option. The essay culminates with an extended discussion of Malcolm X and Ali La Pointe, both of whom began their outlaw careers as thieves and honed their skills for what would become historic leading roles in the Black and Algerian liberation struggles of the mid-twentieth century.

Cultural Intervention

Here a key thrust of Basel’s approach to his revolutionary scholarship is made clear: it isn’t historical analysis as academic exercise or to fill a gap in the literature. And though it may be instructive on an organizational level, its real value is in its potential to transform the way we look at, and interpret, the world around us. Whether it’s through reinterpreting the past or through juxtaposing our own lives to those in the biographical accounts, Basel pushes us to rethink our relationship to such things as authority, the permissible, and the possible. His history of the “‘awna”19al-Araj, 35-46.makes his project of cultural transformation explicit. ‘Awna is a mainly rural Palestinian concept akin to mutual aid, which came into Arabic usage from 1994 onwards as Western-backed NGOs worked to find concepts homologous to their own, and settled on this one as the analogue to “volunteerism.”

In its neoliberal variant, NGOs distorted ‘awna into a glorified version of volunteerism, a way for NGOs to extract free labor while somehow arguing that this was part of “local culture.” Basel saw the danger in this, and sought to fight back by providing an actual history of ‘awna by distinguishing it from lofty notions of altruism that are so central to volunteerism, and by showing that it was part of a set of concepts (like faz’a)20Faz’a, Basel shows, is the broader concept, of jumping to aid someone in need of help. It was commonly evoked in the Nakba by people rushing to aid people and communities coming under Zionist attacks and expulsions. In making sense of the Nakba after 1948, writers blamed the spontaneity of faz’a for the failure to defend Palestinian communities against Zionist aggression, and the term took on a negative connotation of being outdated, unfit and equating to disorganization. In Basel’s analysis, this is why ‘awna rather than faz’a was the term deployed by the NGO sector in their effort to invent a local tradition of altruistic volunteerism. that emerged from the political economic contexts of rural communities banding together in the face of scarcity brought on by greedy landlords and tax farmers. He goes on to show how gender equality and anti-hierarchical organization are central to the notion, and that it is, at its core, about survival rather than lofty humanitarianism. He substantiates his arguments with a stunning breadth of sources that range from etymological texts, popular proverbs, songs and oral histories.

In an even more far reaching essay on “The Palestinian Couch Faction”,21al-Araj, 176-185. he makes a scathing intervention criticizing cynical Palestinian pronouncements on the 2011 Egyptian uprising, which he juxtaposes to the increasing levels of Palestinian inaction in the face of accelerating settler-colonial theft and violence, which he directly connects to the increasing influence of the Palestinian Authority, neoliberal transformation of the Palestinian economy and the breaking of the community into atomized and self-serving economic units as a result of Israel’s apartheid infrastructure.

Lessons of the Past, Fuel for the Future

In “The Economy in the Intifada”,22al-Araj, 53-76. Basel describes resistance as having three parts: direct action (protest, sabotage, etc), popular mobilization and organization and economic self-sufficiency and development. The essay, as its title suggests, focuses on the third pillar in the context of the First Intifada, but emphasizes that each of the three pillars are thoroughly imbricated in, and are necessary for, the success of the others and the overall movement. As with his essays on ‘awna and the Black Hand, Basel is attentive to the merits of non or even anti-hierarchical organization, emphasizing that decentralization and non-hierarchy do not entail the absence of organization.

Basel extends this valorization of decentralized organization down to the immediate tactical level in his discussion of the first intifada. He reminds readers that the street battles between largely unarmed Palestinians and the armed-to-the-teeth Israeli soldiers were not coordinated from a particular center, but were by no means spontaneous, disorganized or without a clear goal. On the contrary, fighters in Jabaliya, Balata, Dheisheh, and Nusayrat refugee camps and elsewhere acquired and held on to basic weaponry and used it in their confrontations with the Israeli military. The militants managed to surround the occupation forces in particular streets and neighborhoods, where they could attack them from all sides. Very often individual occupation soldiers found themselves alone in refugee camp alleyways after being steered there by stone throwers, while the Palestinian strike forces strategically placed themselves on rooftops to either support a particular defensive attack on the invading troops or to break the encirclement by such troops on a particular group of Palestinian militants. Citing Israeli military reports, he shows that the occupation forces would often find themselves under intensive coordinated attack, “hounded from street to street” by stone and Molotov cocktail throwers, just as they had declared an area ‘safe’.23al-Araj, 57. This highly decentralized level of tactical organization made a mockery of Israel’s undeniable military superiority.

Basel offers some historical background to what he characterizes as organized spontaneity. He shows how over the course of the 1970s, annual commemorations, such as the Balfour Declaration or Nakba anniversaries, and martyr funeral processions that became occasions for large rallies. Over time, the resistance tactics then expanded to include special operations (‘amaliyat naw’iyyah) in which the more agile and daring youth developed tactics to obstruct Israeli military patrols and raids. With time, these militants could count on schoolchildren to hinder soldiers’ visibility by burning tires at the end of each school-day. Meanwhile, the engaged population developed the mass tactic of large rallies into city- and country-wide sector strikes and general strikes, culminating in the memorable tax, labor, rent, commercial strikes and the refusal to pay fines and penalties that were a key weapon of the first intifada. The corollary of this non-cooperation, which emphasized the boycott of everything relating to the occupation (which parallels the strategy of ungovernability in the South African liberation struggle) was the emphasis placed on domestic economy in the form of growing food and raising animals at home, and the proliferation of retail, craft, agriculture, community hygiene, public health and educational cooperatives.

With his immense range of reading and knowledge, one of the striking facets of Basel’s writing is its accessibility. In one of his quirkier essays he interweaves the scientific literature on porcupines and mosquitos with stories and memories of villagers’ interactions with these creatures and quotes from Mao Tse Tung and Friedrich Engels to deliver a moral, as if from a fable: “Live as a Porcupine, Fight like a Mosquito”.24al-Araj, 166-169. He was able to bring the most specialized scientific writing into everyday language, and always for the purpose of saying something meaningful. In another, titled “No Love for the Oppressed”25al-Araj, 170-172. he cites no writings whatsoever, but reflects on lessons he had learned from a former lover to come to his own understanding of the ways settler-colonial oppression disfigures Palestinian masculinity into a narcissism that renders women “either prostitutes or tools for the reproduction of little slaves”.26al-Araj, 172. (In another essay on gendered power relations in the collection, “Don’t side with the Occupation against Palestinian Women”,27al-Araj, 191-196. Basel draws on psychoanalysis to argue that Palestinian men take out the frustrations of their own emasculation on Palestinian women who fight back, but struggles with how to address this without alienating ‘broader society’).

Other essays and social media posts contained in the book draw on lessons from other liberation struggles such as the Vietnam and Black liberation movements in the USA and intervenes in the protest movements of the early 2010s that targeted the PA and offers detailed histories of Palestinian resistance operations. Others offer commentary on various topics, ranging from child marriage and forgotten heroes, to how to reckon with Israel’s use of triple action pepper spray. Though variable in length and style, each one has a lesson to teach, each is as engaging as it is carefully thought out and presented, and most leave one with awe at a mind that took seriously the questions “how do we get free?”, “how do we surmount the seemingly-insurmountable power of one of the most powerful militaries in the world that enjoys complete impunity?”, and “how do we become free as people without falling into yet another postcolonial authoritarian patriarchal society?” Basel argues that knowledge, critical analysis and action are all essential to finding the answers, and his writings reveal the depth and commitment he brought to this task.

Towards the Re-enchantment of the World

Of the pieces Basel wrote in his last days – found together with his other writings in the apartment in al-Bireh where he fought off the Israeli soldiers – two in particular stand out. One was a piece titled “Why do we go to War?”.28al-Araj, 326-335. His answer to the question is surprising coming from someone who knows more than most about the crimes of colonialism in Palestine and almost everywhere else. His answer: al-romansiyyah, or romanticism. arguing that the romance of war is by far the most enticing. He supports his answer with examples from Hollywood and Bollywood films to great narratives of struggle from the world over. “All other attempts at explanation are not answers, they are attempts to evade an answer; rationalizations of romanticization”.29al-Araj, 329. Basel surrounded himself with militant intellectuals, and this was his last word to those who would ground everything in Reason, who insisted that any romanticizing of heroism, martyrdom and glory was at best a childish motive, one unworthy of Palestinians’ struggle. Basel’s last words on this:

You, the academically inclined, set your sights on disenchanting all things by defining and explaining, reckoning that it will land you on the truth. In these overcast days I tell you I need no explanatory framework for rainfall – whether it is Thor’s hammer or God’s mercy or meteorologists’ consensus. I want none of it. What I want is my unabating wonder and my silly smile whenever the rain falls. Every time as if the first time, a child bewitched and the magic of the world.

The second is a letter Basel wrote as his final testament when he was sure the Israelis hunting him would kill him. It is from the last passage of this testament that the book is titled, a passage that says everything about where he had arrived in his question-riven romantic quest.30al-Araj, 345.

Greetings of Arab nationalism, homeland, and liberation,

If you are reading this, it means I have died and my soul has ascended to its creator. I pray to God that I will meet him with a guiltless heart, willingly, and never reluctantly, and free of any whit of hypocrisy. How difficult it is to write your own final testament; for years I have contemplated such texts by martyrs, and been bewildered by them. Succinct, and without eloquence, they do not sate our burning desire for answers about martyrdom.

Now I walk to my fate, satisfied that I have found my answers. How stupid I am; is there anything more eloquent than the actions of a martyr? I should have written this months ago, but what kept me was that this question is for you, the living. Why should I answer for you? You should search for it. As for us, the people of the graves, we seek nothing else but God’s mercy.

Hazem Jamjoum is a doctoral candidate in the modern history of the Middle East at New York University.