At the time of writing this review, there is an escalation of the genocide of the Palestinian people on their native, occupied land. The most quoted statistics are those of the deaths, which are rapidly approaching 30,000 people. Less discussed, however, but just as important are the wounded: over 69,000 and counting. Before this escalation, the Gazan population was approximately 2.2 million. That means that over 1% of the total population has been mercilessly killed by Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF). It also means that just over 3% have been maimed. Bombs drop every single hour of every single day, raining down upon the tents within the so-called “safe” zones, where the Palestinian people are sleeping in freezing cold with empty bellies and both terror and grief in their hearts. The campaign against them is relentless in its violence and dehumanisation.

Considering that Gaza already had a rate of disability that surpassed global averages—18.1% of Gazans having at least one chronic health condition and a minimum of 40% of households having at least one person with mental health difficulties—this is a staggering amount of death and injury. We hear reports of, on average, ten children per day undergoing amputations, frequently without painkillers or anesthetization. Israel continues to use white phosphorus, which inflicts excruciating and hard-to-treat burns, often down to the bone. There is, then, clearly a policy that results in extreme amounts of injury if it does not explicitly kill. This is to say nothing about the concurrent violent escalation in the West Bank by both settler paramilitaries and the IOF.

Understandably, it is the staggering death toll and reports of whole families being obliterated that dominate current discourse. However, the sheer amount of injury should also be noted. Across the world, disability is often unfortunately considered a ‘fate worse than death’, partly because many societies are so ableist that any impairments’ biological difficulties are compounded by inaccessible environments and a lack of healthcare, which comes about for a variety of reasons: poor attitudes by doctors based on the hierarchical relationship between doctor and patient, as it the tendency in the Global North; a lack of resources due to ongoing (neo)colonialism, as it tends to be in the Global South; and because of capitalism and its logics of barely maintaining its army of labour across all parts of the world, in particular those places where healthcare is scarce or not free. This is no different in Gaza. Infrastructure is routinely targeted so as to debilitate the population further. We have seen a policy of targeting hospitals specifically to destroy the health services during this escalation of violence. How can someone with mobility issues be expected to traverse a landscape made of rubble? How can treatment for ongoing health conditions, many of which were caused by previous Israeli attacks, happen when even the acute issues caused by the current genocide cannot be treated?

It is no surprise, then, that Israel expresses a policy of maiming the Palestinian population. Indeed, in January 2024, Israeli Heritage Minister Amichai Eliyahu called for Israel to “find ways for Gazans that are more painful than death”. In societies that see disability as an unworthy form of life, it can be said that the current policy has been explicitly designed to cause injuries (let alone the trauma of living under constant bombardment, surrounded by death, disease, and debilitation) to the Palestinian population if they are not killed outright.

Furthermore, it has been reported that every member of the Gazan population is food insecure, with 26% facing catastrophic starvation. Indeed, four out of five of the world’s hungry live in Gaza. Rates of disease are soaring. If the population is not immediately killed, it is starving, it is traumatised, it is injured, it is at risk of illnesses that could prove fatal given the lack of health care, and it is thirsty. We can talk, then, of a population physically debilitated by the genocidal campaign perpetrated against them that shows no signs of abating—indeed, only of increasing. Debilitation of the entire area, both the infrastructure and the people, is the goal.

Situating Puar: Liberating from the Academy

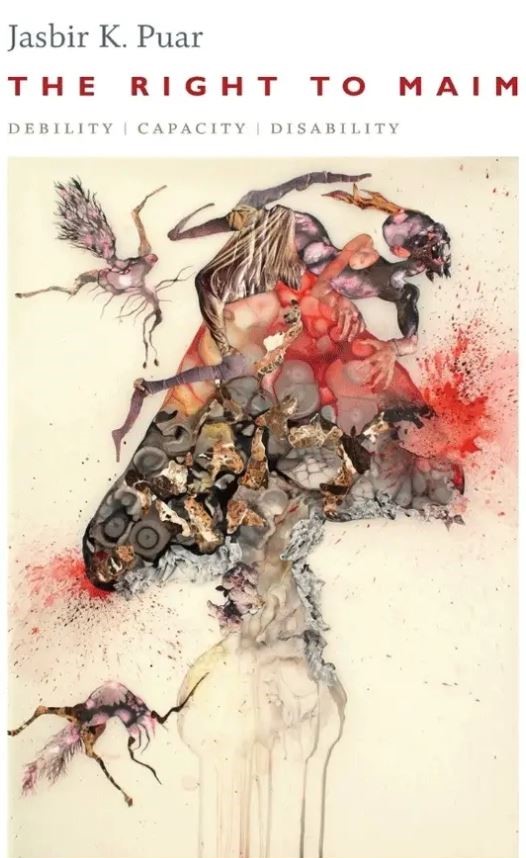

“[D]ebilitation is rendered a fate worse than death”.1Jasbir K Puar, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 140. So says Jasbir K Puar in her prize-winning 2017 book The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. In this, she covers an expanse of topics, from transgender rights to Israeli pronatalism, the solidarity between Black Lives Matter protestors and Palestinians after Michael Brown’s execution, through to critiques of the liberal rights discourses of much disability activism. However, what is of most interest to this review is the centring of Palestine within Puar’s work. Famous for her writing on homonationalism, Puar turns her critical eye to Israel within The Right to Maim, stating at the end that “the ultimate purpose of this analysis is to labor in the service of a Free Palestine”.2Puar, The Right to Maim, 154. Indeed, the ongoing genocide of Palestinians at the hands of Israeli settler-colonists is essential to her work, given that it is the most obvious example of the right to maim and the resultant debilitation of a population.

Firmly settled and famous within academia—she is Professor and Graduate Director of Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutgers University—Puar and her text have been quite well-received within the academy. However, the concepts she names seem to have been mostly confined to usage within this ivory tower. While there are smatterings of the text’s vocabulary on social media during the current genocidal escalation, it is not as widely used in the same way that other theories on disability and the postcolonial violence perpetrated by Israel are. Perhaps part of this inheres from Puar’s drawing on the work of Michel Foucault (among other scholars), who has been rightly criticised in left-wing spaces for a variety of transgressions, including accusations of plagiarism from the Black Panthers. Even ignoring this, however, Foucauldian and other post-structuralist work can be needlessly convoluted and can ignore the material basis of the discourse and power that they speak of. It could be said that The Right to Maim follows in the footsteps of being dense. However, Puar’s use of Foucauldian biopolitics3Biopolitics is the governmental control over life itself, often through means of eugenics. It aims to control society, on the level of population, through the means of biopower (as opposed to on the level of the individual, which Foucault calls “disciplinary power”). Its targets are, quite often, the demographics of a population: birth and death rates, levels of disability, employment figures, and so on. Biopolitics exposes that the field of these kinds of statistics—literally, the science of the state—are in service of capital, colonialism, and other systems of oppression such as racism and ableism, and serve a greater administrative purpose in which the state actively intervenes in these figures. The term “biopolitics” has been picked up by academics to cover a wider variety of phenomena, particularly in fields such as postcolonial studies and academic feminism. is tempered by her usage of other theories, ranging from disability justice studies to postcolonial thought, and it is impossible to say she ignores materiality when a key part of her thesis is on the economic gain made from debilitation. As such, despite its post-structuralist leanings, there is enough materialism contained within the text to please any ardent Marxist. With the theory being so heavily expressed through the analysis of Israeli policy, it is especially prescient today. One could say, then, that the text needs to be liberated and brought into the hands of those outside of the academy who wish to have a wider vocabulary to understand the current crisis.

Debilitation or Disability?

While the two terms may seem synonymous, Puar is at pains to express that debility and disability are related but refer to very distinct phenomena. Disability is an identity, whether one uses the medical or social model (or a combination of the two), particularly in the neoliberal societies of the Global North that attempt to spread their definitions through colonialist means. Debility, however, is a condition of harm perpetrated against a people to biopolitically manage them as a population. It is a process, not an identity. One by-product of this is to leave the debilitated confined to what Lauren Berlant calls a “slow death”: an eking out of life that can barely be called more than survival.4Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011). This is a concept Puar draws on in her definition of debility, although she also argues that debilitation is not the same as, but can instead result in, slow death. Noting that the causes of such debility are related to many of the world’s capitalist and colonialist machinations, such as the military industrial complex, environmental toxicity, prisons and policing, and unsafe labour conditions, she states that “[d]ebility addresses injury and bodily exclusion that are endemic rather than epidemic or exceptional”.5Puar, The Right to Maim, xvii. The word “endemic” here is instructive: Oxford Dictionary defines it as “[h]abitually prevalent in a certain country, and due to permanent local causes” (emphasis added). This means debility is par for the course, part and parcel with the socio-economic and political systems we struggle against.

This may sound like the debilitated are collateral damage. However, Puar explains this is not the case: instead, they are a biopolitically managed outcome of the right to maim, which we shall come to shortly. As Lena Obermaier writes, “[c]ollateral damage implies, as the word suggests, secondary or ancillary harm to the actual objective. However there is very little that is collateral and much more that is deliberate about civilian damage”.

What is important to note here is that debility is purposefully inflicted on marginalised populations. The debilitation (and sometimes murder of these people via slow death) is one way to rid of a population marked as Other who is dehumanised to the point that harm to them is considered a “natural” by-product by those interpellated into not seeing the purposefulness of this process. As Obermaier explains, this is part of a ‘logic of elimination’ that underlies settler-colonialism, in which the entirety of its ideology and praxis is based upon eliminating those deemed as inferior and lacking humanity. Indeed, so dehumanised are those that are debilitated that “[i]t is as if withholding death—will not let or make die—becomes an act of dehumanization [in itself]: the Palestinians are not even human enough for death”.6Puar, The Right to Maim, 141. This is the same for all debilitated populations.

Because debilitation and disability differ, the populations can cross over: one can be both disabled and debilitated. However, the sister concept to debility—capacity—has interesting effects in the Global North. While one might think all disabled people are debilitated, systems of rehabilitation and care within these societies—systems that produce a large amount of profit—can lead to the capacitation of disabled people, enfolding them into the system as docile and productive individuals (both in terms of them working and in the work they generate from their needs). These people are then used by liberal, human rights-based disability discourse as figures of “empowerment”. They are reduced to “inspiration porn”.7While this may sound like a strange phrase, “inspiration porn” has been used within the disabled community for some time now to refer to a very specific phenomenon and is also used by Puar. Popularised as a term by late Australian activist and comedian Stella Young, it refers to the ways in which disabled people’s lives are turned into awe-inspiring narratives or “feel good” human interest stories for the benefit of non-disabled people, who can think “at least I’m not like them” and patronisingly give the disabled person of the narrative a “pat on the back”. It exceptionalises the disabled person in question because they go against a norm that the representation reinforces, one of the personal tragedy of disability that sees disabled life as lesser by dint of the impairments themselves. However, it can also be used as a disciplinary tool against other disabled people in general, admonishing them for not being as successful as their peers on the pedestal. A good example of inspiration porn is almost any advertisement around the Paralympics, but in particular, those run by the UK’s Channel Four for the Rio 2016 competition which heralded those taking part “superhumans”.

Relatedly, one can be debilitated without necessarily being seen as disabled. As Puar writes, the concept of debility “comprehends those bodies that are sustained in a perpetual state of debilitation precisely through foreclosing the social, cultural, and political translation to disability”.8Puar, The Right to Maim, xiv. Because of their marginalisation, these people cannot claim the disabled identity. However, can one call them able-bodied in the same way as someone with other privileges? Puar says no, using Palestine as the example: “[a]s the inhabitants of the West Bank are suffering… no one is constituted as an idealized able body”.9Puar, The Right to Maim, 158.

The material reality of this must be spoken of, too. Just as much as disabled people and the industrial complex of medical care and rehabilitation that surrounds them profits from them, the foregone conclusion of debility is also lucrative, as we shall see below, whether that’s because their maiming is the war machine’s gain, or because the prison industrial complex makes money off of their broken backs. “Debilitation is therefore not just an unfortunate by-product of the exploitative workings of capitalism; it is required for and constitutive of the expansion of profit”.10Puar, The Right to Maim, 81.

The Right to Maim: Israeli Destruction of the Palestinian People and Infrastructure

How is debility produced? Like the sovereign right to kill (which can be defined as “make die” or “let live”) and the biopolitical, eugenicist management of a population’s life (which can be defined as “make live” or “let die”), there is also, according to Puar, a “right to maim” that disturbs the boundaries between sovereign and biopolitical power, operating as both at the same time. As she writes, liberal “humanitarian” figures will define the operation of this right in warfare as a kindly “let live”. However, it truly amounts to a case of “will not let die”.11Puar, The Right to Maim, 139.

The right to maim operates on two levels: firstly, the deliberate physical and mental debilitation of a population. Although Puar does not focus on the psychological effects of warfare and genocide, its realities are deeply traumatic and therefore a form of maiming, too. For instance, one cannot define a Palestinian child’s experience of the occupation as post-traumatic stress disorder because the ongoing bombardment is continuous and never-ending and even in 2003, a report found that 93% of Palestinian children felt unsafe due to the ever-present threat of attack. These mental and physical effects are the most obvious manifestation of the right to maim.

There is also, however, the purposeful debilitation of a population by destroying their infrastructure. As Obermaier says,

Manufacturing health infrastructural disintegration works in three ways: through the deliberate killing or injuring of paramedics and doctors; through the debilitation of health facilities which impose situations of near-collapse; and by expanding the blockade on items necessary for recovery.

If roads are untraversable because of rubble, if healthcare systems are failing because of constant attacks, if a population is starved, if there is no public hygiene, if painkillers and anaesthesia and dressings have run out, the population will be absolutely debilitated even if they do not suffer from physical or mental injury (which would be an astounding outcome, given the level of violence).

All of this, of course, has been happening since the Nakba, being very apparent in the First and Second Intifadas as well as the Great March of Return, the focus of Obermaier’s article. It is unsurprising, then, that it continues to happen in the current genocide and only looks like it will keep on being policy, explicit or otherwise.

Capital Always Finds a Way: The Profitability of Maiming

The debilitation of Palestine and its population is profitable. In the past, rehabilitation of the people and the land has resulted in colonialist corporations making vast amounts of money. Puar explains that this is the way that Palestinians were made to be income generators.12Puar, The Right to Maim, 146. Because of Israel’s reticence to the idea of employing Palestinians,13Puar, The Right to Maim, 147. capitalism demands another way to profit from their bodies. Debilitation offered this up. However, because Israel has now clearly committed to the genocide of Palestinians, there needs to be another way to profit from the destruction. There are already Israelis speculating on what a colonised Gaza might look like if the state were to re-establish settlements there, dreaming up notions about beachfront properties. This total razing of Gaza to make way for the new would create a menagerie of business opportunities for both local and international development companies. There is, of course, also the profiting of the military industrial complex. For example, the infamous Elbit Systems reported an increase in year-on-year profits at the end of the last quarter of 2023, citing an increase in demand, and analysts from Morgan Stanley and TD Bank were eyeing the figures at the beginning of the conflict’s escalation. Indeed, Obermaier explains that the violence against the Palestinian population essentially works as a form of advertising of new Israeli military technology, which then tends to see a boost in sales during and after the conflict’s escalation.

It’s important, here, to point out comparisons to other ongoing conflicts and genocides to show the global nature of our struggles and to build solidarity between the marginalised. There is an ongoing genocide in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in which children have been badly injured in the cobalt mines that produce raw materials for brands such as Apple and Tesla. This is reminiscent of the era of the Belgian colonisation of the region. Then, too, there was forced labour and maiming as punishment. As we can see, then, regimes across the world and throughout history have used the right to maim either instead of or as a supplement to the right to kill in order to biopolitically control a population for primitive accumulation and profiteering.

Injuring Resistance: The Israeli Maiming Policy to Quell Palestinian Uprisings

However, the maiming of the population of Palestine and the destruction of infrastructure serves yet another purpose: the quelling of resistance to Israeli settler colonialism and its ongoing genocidal campaign. As Puar writes:

It is not just the capture and stripping of “life itself” that is at stake here but the attempt to capture “resistance itself.” How much resistance can be stripped without actually exterminating the population? Another question is, of course, what are the productive, resistant, indeed creative, effects of such attempts to squash Palestinian vitality, fortitude, and revolt?14Puar, The Right to Maim, 136.

Israel, in its maiming, is attempting to destroy the morale of the Palestinian people and render them too debilitated to fight back. It is that simple. The right to maim is not just about capitalist profit but the aim of meeting no resistance to their violence. The escalation of the violence that we are currently seeing, and the purposeful maiming of a population if it is not killed outright, is evidence enough of this, considering the line that Israeli politicians and their allies keep spouting about their motivations being only to destroy Hamas. As all civilians have been marked as complicit, they are no longer “innocent”—if they were ever considered that, seeing as racialised populations rarely are. All are seen as militantly resistant to Israel. Hence, the right to maim is utilised to crush any resistance to the goals of Israeli settler colonialism and its programme of ethnic cleansing.

This has been an explicit tactic since at least the First Intifada, in which the “broken bones” policy of then-Israeli defence minister Yitzhak Rabin was implemented. Palestinian Wael Joudeh (whose beating in 1988 was caught on film) described it as them “beating us with every ounce of their energy. They not only wanted to break our bones and to inflict physical pain on us, they also wanted to humiliate us and shatter our spirit”. The same article describes the story of Khadija Abu Shreifa, who fought back against an Israeli soldier for sexually harassing young Palestinian girls at a protest. Because of this, she was beaten and shot at close range in both her shoulder and her foot, now permanently debilitated because of this. Obermaier explains how this form of violence continued into the time of the Great March of Return, during which time 35,450 people were maimed, often with bullet exit wounds the size of fists or even open hands.

As can be seen from these examples, the broken bones policy and disproportionate maiming during the Great March of Return both stand out as a blatant execution of the right to maim being used to quell and deter resistance from the Palestinian people. We can see, then, continuities between the past and the genocidal present.

A Necessary Addendum: Sumud and Everyday Resistance

Does this mean that resistance is crushed? In a word: no. No matter how many bombs drop, how many limbs are amputated, how many families are wiped out, Palestinians still have resistance within their hearts.

A concept that exemplifies this is the notion of sumud, which literally means “steadfastness”. Associated with the well-rooted olive tree, a plant deeply intertwined with Palestinian heritage, sumud is the determination of the Palestinian people to resist, maintain social cohesion, identity and even the capacity for joy, amidst the suffocating violence of settler colonialism. As Yousef Alhelou writes, “Israelis destroy and Palestinians rebuild. Palestinians have, sadly, become accustomed to endure such suffering. This defiance is an act of Sumud and a way of life”. By continuing to exist on the land and forwarding the Palestinian cause in whatever way they can—for example, digging through rubble to save the wounded or working in a hospital while bombs drop all around—the Palestinian people are acting in line with sumud. Wael al-Dahdouh, a journalist for Al-Jazeera, is perhaps the most emblematic example of Palestinians embodying sumud post-Nakba,15Thanks to Alex Turrall for this idea, inspired by this tweet. considering the murder of his family members in targeted attacks by the IOF designed to break him in mind, body, and spirit.

Any form of resistance, of prolonging Palestinian life on their native land and, indeed, the determination to remain on their land, constitutes an attack against Israel’s settler-colonialism. In this respect, the continued fight for survival by Palestinians in the face of overwhelming force makes them samidun.

As Audre Lorde famously wrote, “[c]aring for myself is… self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare”. In the article in which this line is quoted, Sara Ahmed states that “to be a member of some group… can be a death sentence. When you are not supposed to live, as you are, where you are, with whom you are with, then survival is a radical action”. This can be said of the Palestinian resistance. While the language of self-care has been coopted by neoliberalism to sell questionable health supplements and place the onus of mental health care onto the people with mental illness themselves, among other phenomena, its roots refer to the radical act of the social reproduction of everyday life for debilitated people. Applied to the Palestinians, then, it shows that existence is resistance.

Lynsay Hodges is a queer, disabled writer and researcher situated with the sphere of cultural studies. While their primary focus is on surviving sexual violence, they also have a strong interest in disability, mental health, and trauma.