The American journalist Richard Boyle witnessed combat for the first time in South Vietnam. It was 1965 and he was, by his own admission, simply a reporter looking for stories of heroism. For Boyle, the Green Berets were perfect: ready, tough, brave, idealistic. They were the archetypal American heroes. And they made good copy.

So too did the Rangers in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). “Crack professionals, mercenaries in psychedelic rainbow-patterned helmets and day-glo red scarves,” they “had power and they knew it.” That power came from their backing by the United States, whose military advisers and material kept the puppet regime in the South in power in the face of mass public discontent. Boyle went out with them in February 1965. In the Mekong Delta, the Rangers stormed a village in Bạc Liêu, taking all military aged men as prisoners.

An ARVN Ranger captain and an American adviser started interrogating the prisoners. They were all about 14 or 15 years old, and they wouldn’t talk. One of the Rangers kicked the boy in the head hard, bringing blood to his mouth. He wouldn’t talk. He was kicked again. He still wouldn’t talk. A sergeant had two rangers hold him while he stuck his bayonet into the boy’s belly. The boy whimpered but didn’t say anything. He wouldn’t talk. A sergeant hacked away with his blade until the boy died. But he didn’t give up a scrap of information.

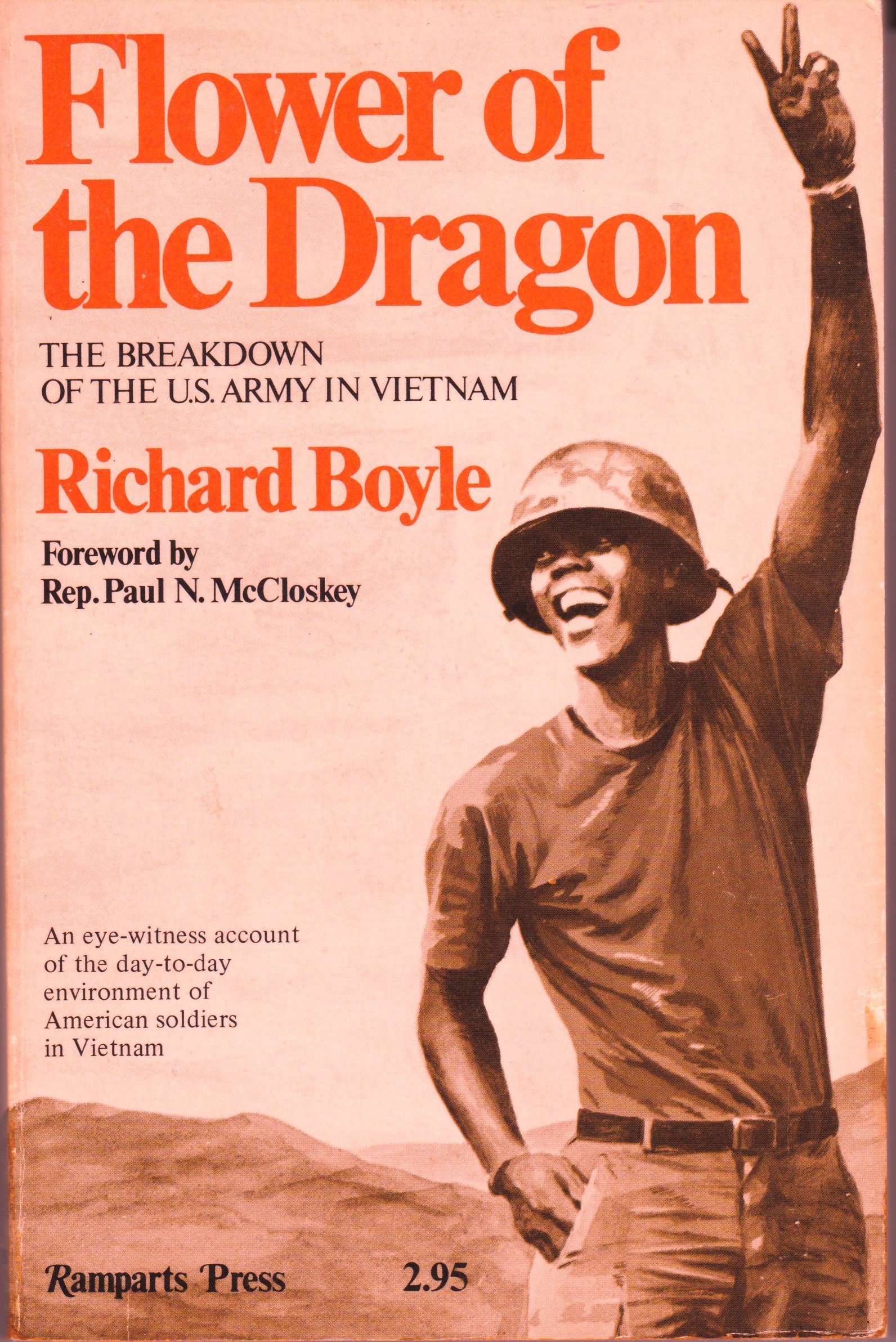

“If I had paid more attention to the faces of the Vietcong prisoners at Bac Liêu or to the way the young men died there, I might have seen things differently,” Boyle reflected in his 1972 book Flower of the Dragon: The Breakdown of the U.S. Army in Vietnam. “But as America marched off to war against the ‘little people,’ I marched with her.”

He’d managed to snap a picture of the soldier standing over the dead boy, captioned “VIETCONG PRISONER KILLED BY RANGERS,” but nobody would buy it.

“Later, back in the States, I sold the photograph with a different caption: ‘RANGER KILLS VIETCONG IN FIREFIGHT.’ It was my first copout of the war.”

Foreign Correspondent

Richard Boyle was an archetypical American war reporter. He’d watched Jimmy Cagney movies as a kid and wanted to be a journalist when he grew up. He’d learned on a series of small newspapers early in his career that the worst thing a reporter could do was get involved in his story. And he’d wanted to see what war was like. So he’d saved up his “meager reporter’s pay” and gotten a visa to go play war correspondent in Vietnam.

There, the US military was the source of almost all stories that American correspondents wrote. As long as you played along, didn’t take pictures of prisoners being tortured, and kept your mouth shut, you’d keep your press card. Without it you couldn’t get on Army bases or rides on helicopters, and you’d be stuck, and you couldn’t work.

“If you went along with the Army it was a good life…” wrote Boyle. “So I went out, took pictures of people dying, came back and sold them, took my money, and went out again. The more suffering, the better the pictures.”

Boyle’s eventual conversion against the war wasn’t the result of anything monumental. He left Vietnam in 1965, hospitalized with hepatitis. He opened a magazine and saw a story about a good soldier friend of his who had been killed. Another war correspondent friend was killed by a landmine around the same time. This made him angry. But it didn’t turn him against the war. Instead, he began speaking out in favor of the war. “I was a hawk,” wrote Boyle, “and I stayed a hawk until 1969, when I returned to Vietnam.”

Before his return, Boyle was peddling an early version of the reactionary spit-on-veteran myth, in which the war was supposedly lost because of dirty hippies jeering at iron-jawed vets betrayed by their country and the crazy kids who greeted them with free love, drugs, and the pill.1This was a fabricated narrative, invented to drive a wedge between the GI movement and the public. In the 1988 book The Spitting Image, the sociologist Jerry Lembcke documented how this narrative was spread in Hollywood and the print media, with the backing of the Nixon administration, despite there being no substantiated media accounts of a veteran ever being spit upon. Lembecke instead documents accounts reported in the media of pro-war activists spitting on anti-war demonstrators, and cites a 1971 poll that shows that 94% of Vietnam veterans reported a “friendly” welcome when they came back to the United States. Yet, between the liberal shoot and cry stories on one side and the spit-on-veteran myth on the other, in Flower of the Dragon, Boyle gives an excellent and deep introduction into a third trend within the largely conscripted Army that was sent to Vietnam. It’s a history that’s been obscured.2Joel Geier, “Vietnam: The Soldier’s Revolt,” International Socialist Review, Issue 9, (August-September 2000) – A working-class army

When Boyle returned, he started hearing about Ben Het, a Special Forces camp deep in the Central Highlands, where Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam met. The 66th Vietnamese regiment, one of the North’s most elite units, was laying siege to this outpost. By 1969, a year after North Vietnam’s successful Tet Offensive,3So-called because it was launched to coincide with the 1968 Lunar New Year celebrations when most South Vietnamese soldiers would be on leave. The campaign inflicted many American casualties and turned the tide of American public opinion against the war. Vietnamizaton was in full effect – so it was the ARVN fighting to hold Ben Het, with just a handful of American troops with them.4This policy was provoked by domestic discontent about American deaths in the war. In response, Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird introduced a policy to “expand, equip, and train South Vietnam’s forces and assign to them an ever-increasing combat role, at the same time steadily reducing the number of U.S. combat troops.” This reduced American deaths drastically, with casualties dropping by 95% over three years.

Boyle went to Ben Het to find the same types of stories he’d looked for when he’d been in the country four years earlier.

But Flower of the Dragon isn’t filled with copy about those “lantern-jawed” Marines and their exploits of American heroism. Instead, he found soldiers exhausted with the war and no desire to fight.

“Hey,” one shouted to him. “Tell the people back home to get us out of here. We’re losing too many people in this stupid, useless war.”

“It was hardly what I expected American troops to say,” wrote Boyle.

He gathered around a dozen troops to see if this was the general sentiment or just the opinion of one man.

“Does what he says go for all of you?” Boyle asked.

“‘Sure does,’ said another, and the rest of them nodded.”

Class Struggle

Boyle kept collecting stories of the side of the war that the Army was eager to keep out of the press. One recurring theme was the “grunts” vs. the “lifers”; the conscripted men and the officer class fighting a low-level shadow war, mounting in intensity year after year.

These eruptions against the ruling officer class began with simple insubordination, but accelerated into combat refusal, striking officers, even killing them, and a rising sense of mutiny. There was a similar sentiment from the side of the officers – if the soldiers were getting ready to fight against them, they’d hit back just as hard. They were already notorious for not caring whether their infantrymen lived or died. Because the path to a plush Army career required combat time for promotion, and because there was such a glut of officers in Vietnam, desperate for a conventional war to advance their careers, they would send conscripted men into battle as fast as they could during their tours.

Combat refusal began, officers were hit, and desertion started to rear its head. A series of court-martials were drawn up to try to suffocate this movement in the crib. Boyle went to report on a series of these proceedings and found that this sentiment was widespread. Even the Army lawyers prosecuting the court-martials hated the war and the Army hierarchy. “It all added up to one thing,” Boyle wrote. “They’d had enough.”

“‘You know,’ General Theodore Mataxis told Boyle, ‘our army is like the army of the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1917.’ As defeat loomed, that army, made up of various ethnic minorities – Czechs, Slavs and Poles as well as Austrians and Hungarians – began to break up into bickering and rebellious factions. There was an obvious parallel, Mataxis seemed to be saying, with the rise of the black liberation movement in the U.S. Army.”

One GI at the Southern coastal city of Nha Trang told Boyle that the basic division within the Army pitted the “heads”5This was a reference specifically to the White GIs who did drugs, but was also a general catch-all term for any of the white soldiers with a countercultural, antiwar, or otherwise subversive perspective. and the black GIs against the lifers on the other side. “The revolution is coming. There is no way to stop it,” he told Boyle. “This place is going to blow, the only question is when. And when it does, every GI is going to have to take a stand. Either with us or with the lifers.”

South Vietnam

One of the virtues of Boyle’s book is that, while it focuses on the GI movement, it doesn’t leave out the South Vietnamese antiwar movement. Instead, it makes a connection between the two and a compelling case for their importance in ultimately ending the American invasion.

In 1971, the class struggle was intensifying across South Vietnam. A massive student protest movement was rising up against the American puppet dictator Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, who was running in elections he had rigged to exclude any opposition. His government was run in the service of the landlords, and enjoyed essentially no support from anybody outside of this rentier class. A seething, raw component in the South Vietnamese peace movement was the veterans who had come home from the front. The class struggle in the ARVN was intense.6A 1966 CIA Intelligence Memorandum observed that “the nearly continuous rise in military desertions, dating from at least 1962, constitutes the most serious manpower problem…of the South Vietnamese Armed forces In the first half of 1966, over 81% of personnel losses in the ARVN were from desertion.7CIA Intelligence Memorandum, 1966, 15. Whole battalions would melt away after combat, with the conscripted men leaving only officers and NCOs behind.

Thiệu responded to the growing uprising the only way he was able to: with massive repression. There were some 200,000 political prisoners in the country – in the notorious Con Son prison they were stuffed in so-called “tiger cages,” where twelve people would share a single cell.

Boyle describes how deserters from the ARVN led their own movement against the war, organizing protests in Saigon, and reaching out to active soldiers urging them to desert too. Ahead of 1970, a Christmas Eve peace march was organized to call for an end to the war on February 5th, the date of Tet, the Lunar New Year in Vietnam.

“The risks, of course, were great. The American Army brass would do everything it could to stop it… there had never before been a demonstration of both GIs and South Vietnamese. If the Hoat Vu [Thieu’s secret police] or National Police fired… and shot American soldiers, the repercussions would be enormous”.

Despite a military media blackout from Stars & Stripes and AFVN, the Army television channel, about 15 uniformed GIs showed up, along with a dozen other Americans. Boyle came not as a reporter but as a participant. The role of the GIs was critical for the march. The South Vietnamese anti-war movement needed news cameras, and only American participants would bring them. The GIs and the newsman’s cameras would provide some small protection to the demonstrators. The American military knew this, so they brought military police to disperse the GIs.

The American press corps at the march ignored the demonstration, or if they did report it they were censored. But the South Vietnamese press printed it boldly, as they started mounting more and more open resistance to the Thiệu regime.

In defiance of the media blackout, an Army broadcaster named Bob Lawrence reported on the cover up of the demonstration. He was court martialed on a trumped up charge, but the broadcast brought more GIs into the anti-Thiệu movement, which heated up and, following an abortive student-led demonstration in January, led to widespread rioting in the spring of 1970.

The country was ready to boil over. The North Vietnamese Army was ready to take advantage of the situation. General Võ Nguyên Giáp, the military genius behind the North’s strategy, prepared an offensive down Route 22 towards Saigon. The offensive was to coincide with Thiệu’s sham elections.

The Road to Saigon

There were three hurdles the North Vietnamese forces would need to clear on their way to Saigon: Krek, Tây Ninh, and Firebase Pace. If any link of this chain broke, they would have an open road to Saigon. Firebase Pace, defended by four long range American artillery rifles, just 300 meters from the Cambodian border, was the most important to defend. The Americans were desperate to prevent it from falling. But if they sent too many American troops to hold the base, high casualties were inevitable, and they weren’t willing to stomach the domestic unrest this would produce.

This was the impact of the anti-war movement, and its effect on North Vietnamese strategic considerations was significant. A document captured in 1969 by the Pentagon’s Systems Analysis Office laid out this logic. The 1969 spring offensive, it said, had been “a significant and great strategic victory… we killed more Americans than we did in the 1968 spring offensive. [It] upset Nixon’s plan, because U.S. forces were heavily hit and their weakening puppet army could no longer provide support for the implementation of neocolonialism. The antiwar movement in the U.S. flared up again strongly demanding the withdrawal of U.S. troops… For each additional day’s stay the U.S. must sustain more casualties…”.8William Shawcross, Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987), 109

South Vietnamese troops were supposed to defend the base, but there was little evidence that they had much commitment to fighting either. The American officers were worried. They knew that they couldn’t get the South Vietnamese conscripts to fight. Still, they figured they would be able to get their own men to go, as long as they didn’t lose too many. But the North Vietnamese troops were battle-hardened and hunkered down. Taking tunnels was a suicide mission with little chance of success. Nevertheless, the officers decided to send out fifteen men. If the radar reports were accurate, they were probably going out against thousands of North Vietnamese troops.

The standard story of heroism would have the troops go out, doomed and aware that they were doomed, to wipe out the North Vietnamese mortar teams. Then the South Vietnamese would be rallied by the courage of the American example, and lay their lives down defending the base against the communists.

But Vietnam wasn’t a movie set. It was a real place with real people — and that is what’s perhaps most refreshing about Boyle’s book. He wrote it when it was happening, and the realism it portrays is not the phony profundity of Hollywood’s depiction of the war, where morally uncertain, dark and confused fare passes for high verisimilitude. Boyle chose instead to look at what he saw and print it, and crucially, he took a side. The officers were monsters, the war effort was murderous and genocidal, and there’s nothing heroic about outnumbered Americans defending a position in service to imperialism and landlordism. What happened next, though, was heroic in a way.

“I Aint’ Going”

As the fifteen men who had been chosen to go out into the night were being given their orders, one of them, named Chris, didn’t listen to the instructions. “Go fuck yourself,” he said. “I ain’t going.”

Five of the other soldiers joined. That crippled the mission. They couldn’t send 9 soldiers out into the night. A court martial was drawn up against the six refusers. But 30 other soldiers got together and voted on it – they weren’t going to let that happen. A veteran soldier with a Zapata mustache, Al Grana, told Boyle “We ain’t lettin’ the lifers fuck over those guys.” They drew up a petition to send home with Boyle to explain why they weren’t fighting. Then they set about getting the signatures of the majority of the company. When the officers tried to reassert discipline, they were met with bored insubordination. An officer tried to get them to clean their guns. “Oh shit, who needs this,” one of the grunts said, then left. The rest of them followed, until the officer was left standing alone awkwardly inspecting his own rifle.

“I wish we could let them know we have nothing against them,” said a grunt about the North Vietnamese soldiers. So they decided to stop fighting. “The men agreed, and passed the word to the other platoons: nobody fires unless fired upon. As of about 1100 hours on October 10, 1971, the men of Bravo Company, 1/12, First Cav Division, declared their own private ceasefire with the North Vietnamese. For the first time since they got to Pace, it was all quiet on the Cambodian Front.”

“To the grunts, it wasn’t the North Vietnamese who were the enemies, it was the lifers… the grunts had the power.” Just like the South Vietnamese soldiers, they weren’t fighting anymore. “The grunts… had the machine guns, the light assault weapons. The grunts outgunned the lifers by about 30 to 1… If it came down to it most of them might join the Bravo Company rebellion rather than side with the lifers.”

A conscript mused about the success of their informal ceasefire. “Today we haven’t done nothin’ but sit here and wait, and they haven’t done anything either. It makes you kind of wonder….”

By this point, the rebellious soldiers had gained the support of most of the other soldiers in their company. Over 50 percent of them were bordering on open mutiny and had signed the petition. Boyle went back to the United States and got the story out to the international press. When the story broke, the Army pulled Bravo company out and relented on the court martials and rotated Delta Company onto Firebase. But then Delta Company heard about the revolt. When a patrol was ordered, 20 men refused to go out. The Army was forced to abandon their base. The road to Saigon was open.

Fragging and Domestic Revolt

While the mutiny at Firebase Pace is perhaps the most dramatic example in Boyle’s book, resistance took all sorts of forms. The most notorious and widespread way that this manifested was in the ubiquitous practice of fragging. Fragging was a way for soldiers to institute discipline on officers who were sending them off to fight when they didn’t want to. They were a semi-formal process of soldier enforced discipline: officers were warned before the fragging took place and given a chance to change their orders. Then, a smoke grenade would be rolled under their bed as a final warning.

In 1972, an Army judge named Capt. Barry Steinberg told Eugene Linden in the Saturday Review that this way of controlling officers was “deadly effective.”

“Through intimidation by threats — verbal and written — and scare stories, fragging is influential to the point that virtually all officers and NCOs have to take into account the possibility of fragging before giving an order to the men under them,” concluded Linden.9Eugene Linden, “Fragging and Other Withdrawal Symptoms,” Saturday Review, January 8, 1972, p. 12

GI underground papers at home played a role too: one told conscripted soldiers not to desert. Instead, it urged them to “go to Vietnam and kill your commanding officer.”

The anti-war movement at home also didn’t confine itself to nonviolent tactics. In response to Stanford University voting to allow a Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program on its campus, riots caused $200,000 in damage to buildings. A militant group on the West Coast carried out large-scale armory thefts against army bases in Oakland. And three soldiers were indicted in 1970 for dynamiting the telephone lines, power plant, and water works of a base in Wisconsin.10Col. Robert D. Heinl, Jr., Armed Forces Journal, 7 June 1971, 30-38.

The story about the informal ceasefire at Firebase Pace was a representative and dramatic moment, but by no means unique. In 1969, a company in the 196th Light Infantry Brigade sat down on the battlefield. Later in the year, a rifle company in the 1st Air Cavalry Division refused to go forward on a dangerous trail, in a dramatic moment aired on CBS-TV.11Ibid. At the Paris Peace Talks in 1971, the North Vietnamese released a statement that they had ordered their own units not to engage with American units that didn’t attack them. And they also claimed that they had American defectors who had joined their ranks.12Ibid.

Conscript Soldiers, Imperial Shadow Wars

In a frank interview with General Mataxis, Boyle received a grim diagnosis of the effect the breakdown of morale and the rise of insurrection had on the American Armed Forces. “We had a good army then,” Mataxis said of the beginning of the war in 1965. “It’s been the opposite of Korea. There we went in with a bad army and came out with a good one. In Vietnam we went in with a good army and came out with a bad one.”

Mataxis also confirmed to Boyle that the fragging campaign against the officers – conscripts against the lifers – had reached such a worrying tempo that the officer class began taking matters into their own hands. A counter-fragging offensive was launched. GIs that had attacked the officers were targeted for reprisal. The campaign began taking on the character of a low level hot civil war, a smouldering insurrection at the heart of the American armed forces.

“What Mataxis was saying was something else” from just scattered reprisals though, said Boyle. “He strongly hinted at a sort of underground movement of lifers, a kind of white guard like the secret organization of Czarist officers who fought the Bolsheviks during the Russian civil war. The lifers knew who the leaders of the GI antiwar movement were, Mataxis said, and his own junior officers knew ‘whom to get.’

Mataxis also spoke about the fear the generals had about the anti-Americanism in South Vietnam. It was, Boyle wrote, at “an all-time high… nobody knew if the ARVN could really be counted on to help.” This worry was so significant that at the time of Thiệu’s sham elections, U.S. high command ordered American troops be confined to their bases, for fear of a massacre by the South Vietnamese people.

Vietnam Vets,…

There were also worries about how the mass of disillusioned veterans would behave at home. Boyle reported some of the sentiment they shared with him when he was back in Washington D.C.

“I killed three hundred VC, man,” he told me, “and you know what I found out when I got back here? I killed the wrong people. Ain’t that a mind blower?”

Then there was Jim, who’d had a chunk blown out of his leg. He told Boyle he felt betrayed by the United States, “sent to bleed in a war to make millionaires richer.”

“There’s something happening, man, it’s in the air, I swear it,” Boyle wrote. “There are about two million vets all over this country, and a hell of a lot of them are getting it together.”

He related a conversation he’d heard from a few bitter veterans at home named Cheyenne, Beagle, and Jim.

“‘Shit, man,’ Cheyenne said, ‘Nixon’s the same as King George.’”

“‘Right on,’” Beagle replied. “‘The people of this country have been fucked over, cheated, and lied to by all of them. Johnson’s the same as Nixon, and Nixon’s the same as Muskie or Humphrey: they all want to screw you.”

“‘That’s what this whole war was,’ Jim said, ‘a big ripoff. Fifty-five thousand guys died to make some people rich.’”

Boyle reflects on this at the end of his book. “It was the troops who pulled off the French Revolution,” he muses, “and it was rebelling soldiers and sailors who stormed the Winter Palace in Russia in 1917. If there are too many more Kent States, or Jackson States, or Atticas, and the people revolt, I think the grunts are going to be with the people, not with Nixon and the lifers. And I think the Pentagon knows it.”13On May 4th, 1970, 4 students were killed and 9 injured at Kent State University during a protest against the US invasion of Cambodia. They were shot and killed by National Guardsmen in a premeditated act. 11 days later, just after midnight on May 15th, Mississippi highway patrolmen and municipal police shot at students protesting in front of a girl’s dormitory at Jackson State College, a predominantly black school. They were protesting racism in the state government and the US invasion of Cambodia. One college student and a local high school senior were killed, and 10 others were wounded. The street they were shot on was called Lynch Street. A year later, on September 9th, 1971, at the Attica Correctional Facility near Buffalo, New York, a prison revolt began which demanded better conditions and the removal of the racist warden. The prison, whose inmates were 54% black, was staffed by all-white prison guards, notorious for their racism and mistreatment of the inmates. Five days after the revolt began, Governor Nelson Rockefeller launched a “military attack” to retake the prison. 31 prisoners and 8 guards were killed in an assault led by a heavily armed 1000-strong force of National Guardsmen, prison guards, and local police. News reports initially claimed that the guards’ throats were slashed by prisoners, but autopsies showed that it was gunfire from Rockefeller’s assault force which had actually killed them.

Maybe this was where the twin narratives of the stab in the back and the spit-on-vet came from: the fear from the U.S. ruling class of a mass of embittered, disillusioned young men with military training who’d developed, in the jungles and mountains of Vietnam, a class consciousness which crystallized the antagonisms the United States and the world was (and remains) riven by into a simple formula: lifer vs. grunt. Conscript vs. officer.

…The United States vs.

Back home there were a bevy of obstacles erected against the furthering of this political education. The spit-on-veteran was a myth, but one targeted at rupturing growing bonds between the G.I. movement and the rest of American society. And it wasn’t hippies or the New Left who “betrayed” the GI movement by pushing class conscious and politically developed veterans out of their ranks. Boyle writes in his book how radical veterans were viewed as politically unreliable to the prerogatives of a thoroughly bourgeoisified US society. In New York State, the Chamber of Commerce printed a pamphlet instructing businessmen not to hire veterans. The pamphlet claimed this was because veterans were all junkies.

But maybe this wasn’t the reason. Maybe so many Vietnam veterans were pushed into homelessness and addiction, out of jobs and onto the streets, because they represented a huge mass who hated the war and were ready to revolt.

And maybe it was because they represented a disillusioned, oppositional force that might not be able to be whipped into the discipline of the labor regime back at home.

A March 1978 article in The Atlantic called ‘Soldiers of Misfortune’ detailed how the administrative apparatus of the state ensured that these potentially revolutionary subjects were immiserated, isolated, and alienated. In the fall of 1974, Vietnam-era veterans accounted for a full ten percent of prison inmates. Up to 150,000 men were given dishonorable discharges, a highly undesirable status for most employers. Anything but a fully honorable discharge made businesses wary. The most common reason for a general or dishonorable discharge was “character and behavior disorders.”

Even soldiers who received fully honorable discharges could be designated a “misfit” if their discharge forms were stamped with the code “SPN,” marking around 200,000 veterans politically unreliable and potentially subversive. The military claimed these codes were used only for internal military use, but the Atlantic reported there was “overwhelming evidence that the key to deciphering the codes fell into the hands of many civilian employers.”

Not only did the SPN number ward employers off from hiring politically unreliable GIs, but it also denied them access to treatment and education. SPN marked GIs weren’t allowed access to VA drug treatment facilities, they weren’t able to go to school on the GI bill, and they were excluded from VA hospitals. If the vision of the Vietnam vet in popular culture is a drug addict huddled on the street in a heap of rags, it’s more likely than not that he’d be the recipient of an SPN.

What this all meant was that, in Vietnam, the U.S. military saw subversive soldiers as a threat to their anticommunist mission. As links were forged between the North Vietnamese Army, the peace movement, and the GI movement, America’s calculus in Indochina shifted, with the threat of mutiny among the enlisted men significantly constraining the operational capacity of the officer class. Then, back at home, anxious about the possibility of soldier revolts and a militant black power movement, GIs were caught up in the drug war launched against black radicals by the state,14Aide says Nixon’s war on drugs targeted blacks, hippies, CNN, March 24 2016 and were further excluded from the national body by administrative coercion.

Lessons Learned

The war ended, and the United States learned their lesson. Never again would they trust a conscript army in a colonial war. Paul McCloskey, a nominally anti-war California Republican who entered Richard Boyle’s record of the Firebase Pace grunts into the Congressional Record, articulated well the fear that the GI soldier revolts represented to the US ruling class.

“There is a growing danger of confrontation between American troops and their officers,” McCloskey told a press conference at the Capitol building in 1971, “which could prove ugly and disastrous.”

Ugly and disastrous for the American Empire, no doubt. Reading Boyle’s book helps us excavate a moment in the history of the American military where its commanders were terrified that a growing consciousness in its conscripted members could be hitched to the ideological leadership of a movement ready to cut off the head of the snake of the American Empire. All successful revolutions are marked by the mass breakdown of discipline within the national or Imperial armed forces. The United States military read its history, and knew the danger that a conscript revolt in a colonial war could pose. The American ruling class applied these lessons and managed to hold off a similar process from being carried out in America’s Indochinese twilight. Boyle’s book is a remarkable document of just what it is they were so afraid of.

Marlon Ettinger lives in New York. You can follow him on Twitter @MarlonEttinger.