It has been almost twenty years since the Abu Ghraib scandal first shocked the world. Photographs exposed United States soldiers gleefully torturing helpless Iraqi detainees in the most grotesque, denigrating ways imaginable. Some of these images became particularly infamous, such as those featuring former U.S. Army Reserve soldier Lynndie England. In one, England can be seen posing alongside naked men piled into an obscene pyramid. In another she drags a man by a leash. His face is contorted in agony and humiliation while England looks on with contempt. And, of course, there is the photograph where a smirking England gestures towards the penises of hooded naked men lined up in a row for the soldiers’ sadistic amusement.

But out of all the vile images to emerge, perhaps the most infamous is of Ali Shallal al-Quasi being tortured. He stands precariously on a block above a pool of what is most likely urine. Wires attached to his hands clearly show he is being tortured by electrocution. His Christ-like pose makes the image all the more haunting. As infamous as this image is, however, you wouldn’t know it was al-Quasi from the photograph alone. A black hood hides his identity, which points to another way these and all who endure torture are made to suffer: their individuality is stolen. Even those whose faces are not obscured are lumped together, reduced to the level of sub-human creatures by their torturers. When we consider these anonymous victims, we are confronted with the reality that there are countless others across the globe whose names we cannot forget because we will never know they existed at all.

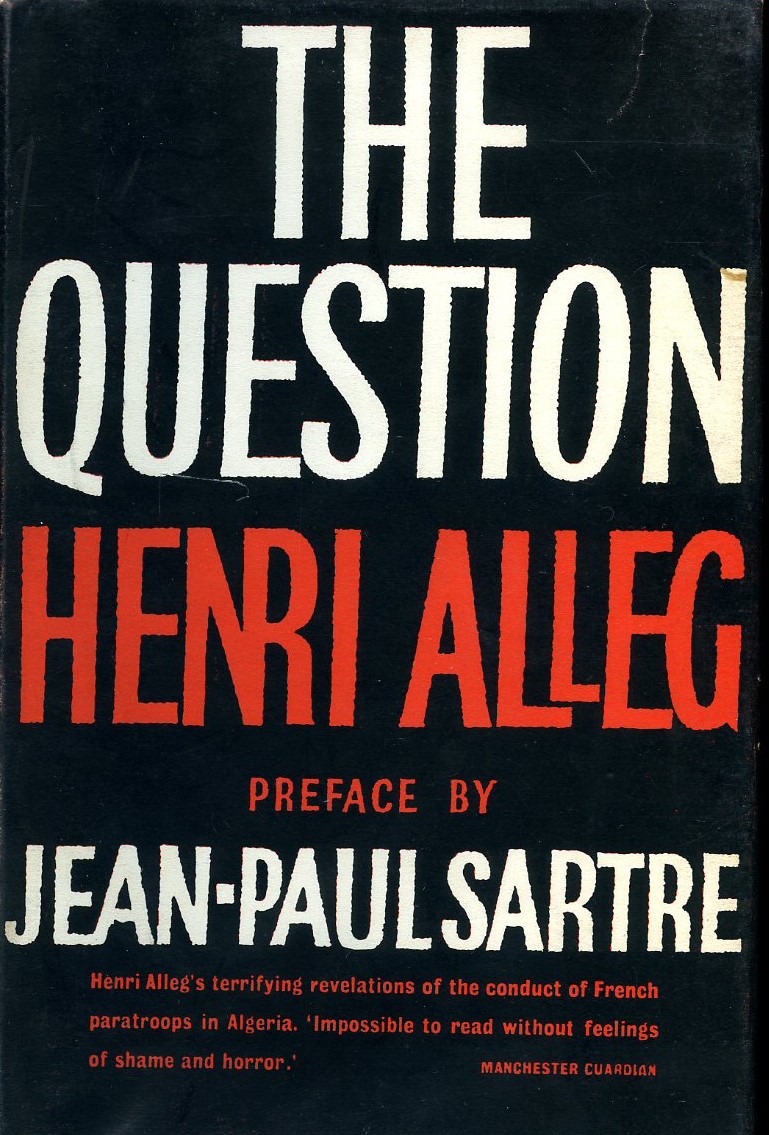

It is the duty, then, of everyone who supports anti-imperialist movements across the world to listen to and cherish the rare voices that manage to escape oblivion. One such voice belongs to Henri Alleg (1921-2013), whose 1958 work La Question remains a vital first-hand account of the vile lengths the state will go to oppress the enemies of imperialism. It is also a testament to the astounding courage individuals are capable of in the midst of so much brutality, inhumanity, and madness. But above all else, it demonstrates the revolutionary power inherent in books. Its influence is not merely theoretical—this is a book that has literally saved lives—and we must resist those who have worked for decades to rationalize torture and obscure what it revealed, by having the courage to read and remember all that Alleg experienced himself.

‘No, I’m not afraid.’

Henri Alleg was a French citizen and communist living in Algeria during the Algerian War of Independence. He supported the Algerian struggle and edited an independent leftist newspaper, Alger républicain, which France had banned in 1955. Alleg went into hiding but was eventually arrested by French paratroopers for publishing banned material. They began torturing him immediately. Alleg’s ordeal would last an entire month.

The torture Alleg suffered can be broken into three distinct phases. The first consisted of brutal sessions that began with electrocution. Strapped to a vomit-stained board, Alleg had clamps fastened to his ears, hands, and later his penis. Paratroopers sent wave after wave of excruciating current through the clamps, occasionally throwing freezing water over his naked body to increase the intensity. When they saw him shivering, they asked if he was afraid. Alleg answered, ‘No, I’m not afraid.’1Henri Alleg, The Question, (John Calder Publishers, 1958; Forward, introduction, and afterword, University of Nebraska Press, Bison Books, 2006), 42

At this early stage, the first signs of the soldiers’ desperation already began to show. They started by making jokes, referring to him as their ‘customer.’2Alleg, 40. A few who did not directly participate came just to enjoy the show. But when Alleg remained silent even after multiple rounds of electrocution, they grew frustrated. In his torturers’ eyes, ‘this was going on too long.’3Alleg, 47.

In addition to undergoing further electrocution (including one session where wires were placed in his mouth), Alleg was beaten, waterboarded, hung upside down while his nipples and penis were burnt, and was tempted with putrid water after being severely dehydrated. In the fleeting hours when he was allowed to sleep, he did so on a mattress stuffed with barbed wire. Still Alleg refused to talk.

More cracks in the paratroopers’ false bravado appeared. At the end of the very first night, one admitted that, even if Alleg eventually talked, ‘he has gained a night for his friends to get away.’4Alleg, 52. Later, another soldier suggested gagging Alleg. When he was told, ‘[Alleg] can shout as much as he wants, we’re three floors underground,’ the soldier insisted, ‘all the same… it’s disagreeable.’5Alleg, 55. The torturers were frustrated even more when their threats to torture Alleg’s wife and children elicited no response. Baffled by Alleg’s resolve, they assumed he didn’t care about his own family. The truth, Alleg writes, is that he was simply too numb from the torture to respond to anything. Alleg was relieved to find that they thought he was indifferent. In reality, the fear that they would torture his wife and children weighed on him far more than they had suspected.

The second phase was more insidious. Seeing that no amount of pain could break Alleg, the paratroopers decided to drug him with a truth serum. A doctor, whose participation makes him as guilty as those who beat, burnt, and electrocuted Alleg, administered the serum. Alleg recalls feeling drunk. Yet he resisted, refusing to endanger his comrades when the doctor tried to trick him with deceptively benign questions.

The final phase revealed the pathetic state to which the paratroopers were reduced in the face of Alleg’s courage. Officers visited Alleg to pontificate about the benefits of French imperialism, arguing that the Algerians were the real enemies, that they had compelled the French to take these extreme measures. Their hollow, trite talking points had no impact.

Around this time, Alleg’s torturers expressed a growing, if reluctant, respect, summed up in the following exchange:

‘Were you tortured in the Resistance?’

‘No, it’s the first time,’ I replied.

‘You’ve done well,’ he said with the air of a connoisseur. ‘You’re very tough.’6Alleg, 82.

It is a gross understatement to call Alleg ‘tough.’ But his resolve was undoubtedly buoyed by his fellow prisoners. An unnamed man was accidentally put in Alleg’s cell. ‘He held me,’ Alleg writes, ‘so that I could get down on my knees and relieve myself against the wall, and then helped me to stretch out. “Lie down, brother, lie down,” he said to me.’7Alleg, 59. A group of Algerian prisoners passing him in a stairwell said, ‘Have courage, brother!’ and in their eyes he ‘read a solidarity, a friendship, and such complete trust that I felt proud, particularly because I was a European, to be among them.’8Alleg, 92. Even those prisoners on the ground floor, condemned to death, retained their dignity to the end. In fact, ‘there is not one of them,’ Alleg asserts, ‘who does not turn on his straw mattress at night with the thought that the dawn may be sinister… Yet it is from this section of the prison that the forbidden songs are heard every day, those magnificent melodies that always spring from the hearts of a people struggling for their freedom.’9Alleg, 33.

‘They must know what is done in their name.’

Alleg emphasizes multiple times that his experience ‘is not in any way unique… what I am saying here illustrates by one single example the common practice in this atrocious and bloody war.’10Alleg, 34. It is commendable that Alleg does not let his personal torment blind him to the ongoing torment of others. Yet he also recognizes that his case is undeniably unique in one way, which is that ‘it has attracted public attention.’11Alleg, 34. The impact this public attention would have on the Algerian War of Independence, French society, and the world for generations to come cannot be overstated.

La Question was written a few months after his transfer from the torture chamber in El Biar, a suburb in Algiers, to a detention camp. It was naturally difficult to write. However, Alleg explains that he dredged up these terrible memories because ‘they must know what is done in their name.’12Alleg, 96. It was also difficult to get the book into the hands of readers. It had to be smuggled out of the prison, sometimes in individual pages, and first published in Switzerland in 1958 before being smuggled back into France in the same year. The government predictably banned it (James D. Le Sueur notes in the introduction that it ‘has the distinction of being the first book banned in France since the eighteenth century.13James D. Le Sueur—quoted in Alleg, xiv.’). Just as predictably, the government was utterly incapable of stopping the book from spreading across France and beyond. Not long after the French edition was published, La Question was ‘translated into Italian, Dutch, Japanese, Czech, German, Hungarian, Romanian, Polish, Russian, and other languages.’14James D. Le Sueur—quoted in Alleg, xv. The first English translation also appeared in 1958, though it would not be until 2006 that another edition was published.

French citizens were outraged, in part because Alleg ‘was an important French writer and communist activist living in Algeria’ and therefore they ‘could identify with him more than they could with Algerian nationalists undergoing similar horrors.’15James D. Le Sueur—quoted in Alleg, xvi. They were also outraged because Alleg had revealed for the first time that ‘torture, once accepted in “exceptional” circumstances,’ was used routinely by the military.16Ellen Ray—quoted in Alleg, ix. Torture is obviously repulsive to any decent human being. But French readers in the late 1950s would have recognized a particularly disgusting irony. Less than twenty years earlier the Gestapo tortured members of the French Resistance. Yet here were French soldiers using precisely the same excruciating methods not in the cause of liberation, but to further oppress a county that had already suffered years of degradation, deprivation, and savage racism.

Not long after its publication, Jean-Paul Sartre wrote a famous essay, entitled ‘A Victory’, which expounded on the significance of La Question. ‘By intimidating his torturers,’ Sartre argued that Alleg had, ‘won a victory for humanity against the lunatic violence of certain soldiers and against the racialism of the settlers.’17Jean-Paul Sartre—quoted in Alleg, xliii. At the same time, he had stripped away any illusions that might have lingered from the days of the Resistance that the German torturers were inherently evil and the French inherently good. Rather, Alleg had revealed that, ‘anybody, at any time, may equally find himself victim or executioner.’18Jean-Paul Sartre—quoted in Alleg, xxviii. Former victims were, and are, not exempt from this disquieting truth.

La Question, then, played a crucial role in ending the practice of torture in Algeria in a number of ways. As one of the first texts to speak openly about the widespread use of torture, it united activists, writers, intellectuals, and the wider public in opposition to the state. Even a military officer, General Jacque de Bollardière, ‘denounced the state for its torturing of Alleg.’19James D. Le Sueur—quoted in Alleg, xvi. Widespread protests by French citizens pressured the government from within, while France’s legitimacy was undermined as countries around the world learned about their crimes. In short, it ‘became a crucible for public protest against the French military’s methods’ in Algeria.20James D. Le Sueur—quoted in Alleg, xvi.

Alleg may insist that his own experience is not significant in itself and grimly wonder: ‘who can tell of all the other atrocities that I have not seen?’21Alleg, 36. But by the same token, who can tell how many atrocities he prevented?

‘The French question has now become a question for us all.’

The French public might have been appalled by La Question as soon as it was published, but that has not prevented the French state and capitalist class from doing its best to erase the history that Alleg struggled to uncover. Over the past fifty years, university curriculums struggle with how to teach colonialism. A law was passed in 2005 that called for ‘teaching the “positive role” of French colonialism overseas and the military’s “sacrifices,” especially in North Africa.’22James D. Le Sueur—quoted in Alleg, xiv. In other words, the same old despicable narrative about how the colonizers actually do the colonized a favor by introducing them to civilization.

While apologists continue to try and debate the issue of torture, the actual practice of torture continues, in part thanks to the French army. It proved ‘impossible to bring anyone involved in Algeria to court for crimes against humanity,’ thanks to Charles de Gaulle’s amnesty. It would be horrible enough to know that these torturers escaped justice. But the tragedy goes further. After the Algerian War of Independence, these very same men went on to advise militaries in Latin American dictatorships and the U.S. during the invasion of Vietnam ‘in their special methods of “interrogation.”’ This relationship calls to mind how, after World War II, many high-ranking Nazis became part of the U.S. military-industrial complex through Operation Paperclip.

As the largest and most powerful empire in the world, the U.S. has been able to perpetrate torture in various countries in flagrant violation of the 1984 United Nations Convention Against Torture, which the United States ratified in 1994. They are able to do so mostly because the U.S. government does its utmost to hide its crimes. Yet now and then the public is made aware of these crimes, as with Abu Ghraib. Guantanamo Bay is another torture chamber that is marking the twentieth anniversary since taking in its first prisoners. ‘The whole place appears to be one giant human experiment,’ according to a law professor representing one of the detainees in Guantanamo Bay.23Ellen Ray—quoted in Alleg, x. But the wider public knows very little about what goes on in that dungeon so close to the U.S. mainland. It’s difficult, if not impossible, to even know who its detainees are. Many have been imprisoned for decades without ever being charged with a crime. But thanks to Alleg, we can surmise what kinds of ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’ are being inflicted in the name of imperialism.

Guantanamo Bay is far from the only place where the U.S. tortures detainees. Given the breadth of the U.S. Empire, it is impossible to know the precise number of such facilities, known as ‘black sites.’ However, a UN report determined the CIA operated black sites in at least twenty countries, ‘including Thailand, Poland, Romania, Lithuania and Kosovo.’ A report by the Bureau of Investigative journalism shed further light on these black sites, including how “deeply implicated the UK was in the overall running of the CIA’s torture network.”

It’s worth noting that Alleg withstood torture in order to withhold information in service to the Algerian cause. Given how little we know about the captives in Guantanamo Bay, it’s entirely possible most if not all of them have no information to withhold, making their pain all the more outrageous.

It’s also worth noting that the practice of torture is not confined to dungeons discreetly kept out of sight. In the U.S., which imprisons more of its own population than any other country on Earth, prison guards are free to indulge their most sadistic impulses. Darren Rainey found out just how far guards can and will go when he was murdered in 2012. Not content to simply shoot him, they locked Rainey, a fifty-year old man with schizophrenia, in a room under a shower. The guards controlled the temperature. They burned him alive. Other prisoners were later forced to ‘scrape chunks of the dead prisoner’s burned-off flesh from the cubicle floor.’ Yet the medical examiner concluded that Rainey’s death was an “accident.”

La Question is important not only as a historical record. Rather, it explores a disturbing practice that existed long before the Algerian War of Independence and has continued to exist long after. It is perpetrated by the United States and other nations, ostensibly in the name of freedom and peace. This will continue as long as the public tolerates it, and we are far more likely to tolerate it if we don’t know it is happening. Imperialists everywhere are counting on our ignorance.

We must hold onto the kind of outrage that Alleg’s first French readers felt. We cannot become numb in the face of torture, no matter how difficult or inconvenient it is to confront. ‘The French question has now become a question for us all,’ along with countless other victims whose stories we will never know— but deserve an answer.24James D. Le Sueur—quoted in Alleg, xxiv.

Matthew James Seidel is a musician and writer currently based in Rochester, NY. His essays and reviews have been featured in Ebb Magazine, Current Affairs, AlterNet, and The Millions.