We revolt simply because, for many reasons, we can no longer breathe. – Frantz Fanon

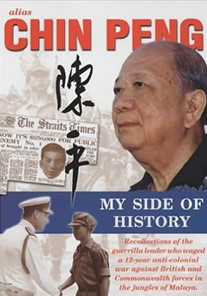

Chin Peng’s My Side of History[1] lays bare the violence of British imperialism in Malaya – violence that robbed the colonised of their humanity and sought to erase their collective memory. The book also affirms the fact that the British colonial state – whose raison d’être was to plunder – was the initiator of violence and therefore the resistance of the colonised to its oppressive rule was a legitimate response necessary to liberate their motherland and reclaim their dignity.

Chin Peng, the nom de guerre of a former leader of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) who lived in exile for decades in Thailand and was once declared the British Empire’s public enemy number one,[2] remains a controversial figure to this day. Not only did the Malaysian government deny him citizenship until his last breath, it also prohibited his ashes from being brought back to Malaysia when he died in 2013. However, just as Chin Peng managed to move around undetected between Malaya, Singapore, Vietnam, and Thailand during the height of imperialist wars in Southeast Asia, his ashes, too, somehow managed to find their way back to the country that he longed for, six years after his death.

Chin Peng died a “stateless alien” in a foreign land. When his ashes were eventually returned in 2019, they were scattered in the sea near the coastal town of Lumut and the jungles of Titiwangsa mountain range in the state in which he was born and raised, Perak. Those who were involved in performing the post-death ritual were then subjected to a police investigation. As news reports about the return of the ashes flooded in, the public sphere was abuzz with anti-Communist sentiments intrinsically linked to anti-Chinese racism, the roots of which can be traced back to the British colonial period.

Confronting British Propaganda

Chin Peng, whose birth name was Ong Boon Hua, decided to write what he described as “the recorded journey of a man who opted to travel along a different road to pursue a dream he had for his country”.[3] Before writing My Side of History, he examined declassified British government reports on the so-called Malayan Emergency – which lasted from 1948 to 1960. This allowed the guerilla leader to have more clarity as to what British officials “in the late 1940s and 1950s were hatching to further the cause of their anti-insurgency campaign against the Communist Party of Malaya”.[4] It also allowed him to evaluate the propaganda the world was fed as he and his comrades were braving the unforgiving jungles of Malaya under the harshest of conditions.[5] The enormity of imperialist propaganda – which had successfully labelled him and his comrades “terrorists”; a label that continues to be used against them today – had to be confronted.

My Side of History, which took five years to write (1998-2003), seeks to unveil “aspects of the [Malayan] Emergency that had yet to be revealed” as the guerrilla leader “held the key to this unexplored territory”.[6] It serves as an important historical document that challenges the dominant historical narratives produced and sustained by Britain’s unparalleled propaganda machine during that catastrophic time.

The British Empire’s Public Enemy Number One

The autobiography starts with the Japanese invasion of Malaya in 1941 which forced the British to negotiate a deal with the CPM (at the time represented by the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army) to fight “a common enemy”.[7] Between 1942 and 1945, the British regarded the CPM as its ally, and interestingly, as Chin Peng emphasises, “[n]ot once did they suggest that killing a Japanese would make us ‘murderers’”.[8] Striking a deal with the CPM was “an intensely embarrassing predicament” for the British as it had to acknowledge that the party “was the only functioning resistance on the peninsula”.[9]

The deal, which gave the CPM access to British weapons, ammunition, funding, uniforms and medical supplies – in Chin Peng’s words, “practically everything we needed to equip our guerrilla army”[10] – was “never anything more than a transient arrangement”.[11] He knew from the start that the British would turn against the CPM once the Japanese aggressors were defeated and, therefore, the party had to be prepared to face the imperialists again. In its effort to obliterate the fierce resistance mounted by the communists, in May 1952 the British declared Chin Peng – upon whom it had bestowed two campaign medals and an Order of the British Empire (OBE) for fighting against the Japanese – to be the British Empire’s enemy number one with a bounty of M$250,000 on his head.[12]

A Childhood in Racially Segregated Malaya

Before discussing the events that led to and took place during the counter-insurgency war which the British referred to as the “Malayan Emergency”, Chin Peng, who became Secretary General of the CPM at the age of just 23 – offers an intimate look into his childhood in a racially segregated Malaya and the path that led him to Communism. He states, “[a]t a very early age I became aware of poverty and the power of money”.[14] The Great Depression, which almost bankrupted his father[15] and witnessing how the British ill-treated indentured Indian labourers made him conscious of human suffering under colonialism and capitalism.[16]

Learning about China in primary school from textbooks printed in that country piqued Peng’s interest in its history and politics. He was only 7 or 8 years old. The textbooks, however, were heavily censored by the British colonial government. The British, he writes, “didn’t want us to read the words like ‘imperialists’ or ‘imperialism’, ‘aggression’ or ‘invasion’”.[17] “Sometimes whole pages were ripped from the textbooks”.[18] Although class discussions about what was unfolding in China were banned by the British, it was still regularly raised and discussed by teachers and students in subjects such as general knowledge and Chinese literature.[19] Group discussions organised by societies he was involved with focused not only on China but also the question of race in Malaya and Asia in general.

Chin Peng became increasingly active in his school activities. At the age of 14, he was elected general affairs officer of his school’s student union. He was tasked with managing library facilities, forming a reading club, and organising student competitions. Under his leadership, the reading club attracted a lot of interest. Through this club he discovered the Chinese translation of Red Star Over China by Edgar Snow. Other books that also influenced him were Soviet Democracy written by Anna Louise Strong and the banned Chinese language edition of The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Joining the CPM

Interestingly, Mao Tse Tung’s On Protracted War – a handbook on organising and guerrilla tactics; on how to defeat the Japanese – made Peng abandon the dream of joining the Kuomintang military college and begin to think about going to China to join Mao’s army. It was during a month-long vacation in Lumut in mid-1938, “somewhere between reading on Marxist theories in the humid confines of the first-storey room and the relief of those lazy moments on the jetty” that he resolved to dedicate his life to the communist cause.[20] He became a member of the CPM at the age of 16 amidst intense anti-communist crackdowns – an age where he decided to carry the weight of the world on his shoulders.

Chin Peng joined the CPM ten years after its formation in 1930. It is noteworthy that Ho Chi Minh was instrumental in its founding.[21] Initially, the party centred most of its operations in Singapore as union movements were more active on the island than other parts of the Malayan peninsula. Given its immense influence, the Straits Settlements Police[22] launched massive crackdowns on the party in the 1930s resulting in five of its leaders being banished to China. The incessant persecution forced the party to constantly shift their base of operations. When the Japanese invaded Malaya, Chin Peng was appointed political commissar in charge of one of the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese guerrilla forces.

The British Return to Malaya in 1945

My Side of History contextualises what the British called the Malayan Emergency by discussing in detail the oppressive actions taken by the colonial state shortly after returning to Malaya and Singapore in 1945 following Japan’s surrender. It is worth highlighting that the first move made by the “temporary form of government” for Malaya and Singapore called the British Military Administration (BMA) – established after a Royal Navy convoy reoccupied Singapore on September 5, 1945 – was to devalue the Japanese currency. This move plunged the working masses into destitution. Chin Peng observes how “food supplies dwindled and prices soared”.[23] Malaya soon became “a cauldron of simmering discontent”[24] as crime rates spiked and corruption festered in the BMA.[25] He further observes how “gangsters, secret society members, strikebreaking labour contractors, planters, miners and the like” took advantage of the ensuing chaos. In light of these devastating conditions, the CPM moved to organise the masses in all states on the Malayan peninsula to form people’s committees and unions for workers, women, and youths.

Popular Resistance to British Oppressive Rule

The BMA’s blatant disregard for those suffering the indignity of poverty and hunger was laid bare the following month when members of the colonial administration decided to increase wages to a maximum of only 33.5 per cent while the prices of basic goods were soaring by several hundred per cent from the pre-war period.[26] This decision, Chin Peng explains, generated massive public outrage, and resulted in Singapore’s first post-war strike involving 7,000 wharf labourers who “refused to work on ships in the Tanjong Pagar docklands”.[27] It is important to highlight that the labourers were not only demanding a 40 per cent pay increase, plus bonuses, but they were also protesting against “handling ships carrying arms for Dutch troops” fighting Indonesians who were involved in the struggle against Dutch colonialism.[28] In the same month, “more than 20,000 workers crammed into the island’s Happy World amusement park for the formal inauguration of the Singapore General Labour Union (SGLU)” to express their solidarity with both the striking labourers in Tanjong Pagar and the liberation movements in the Dutch Indies and Indo-China.[29]

What is revivifying about these collective actions is how the weight of the shackle of colonialism wrapped around the masses’ necks did not stop them from doing everything in their power to stand with those who were brutalised by the same shackle in other parts of the world. “Across the Causeway, in Malaya”, Chin Peng observes, “the numbers of participants in demonstrations and rallies grew alarmingly”.[30] Women participated in mass demonstrations demanding “rice and a government handout of $20 to rescue their families from destitution”.[31] Hunger marches swept all over the peninsula, posing what Peng describes as “a very serious threat” to the BMA’s authority.[32] The severity of the situation that was engulfing Malaya can only be understood against the backdrop of its exploitable wealth. As Britain’s Colonial Secretary Arthur Creech-Jones noted in July 1948, Malaya “is by far the most important source of dollars in the colonial empire and it would gravely worsen the whole dollar balance of the sterling area if there were serious interference with Malayan exports”.[33]

The So-called Malayan Emergency

Chin Peng proceeds to highlight how Western historians writing about the so-called Emergency “frequently begin their accounts” with the killing of three British planters in Sungei Siput in June 1948 “as if the violence began there”.[34] Calling that “a convenient beginning, but historically quite inaccurate”, he reveals that the violence, in actuality, started in October 1945 when “British troops were called in to disperse large demonstrations involving tens of thousands of unarmed people in Sungei Siput, Ipoh and Batu Gajah” in the state of Perak.[35] The troops fired directly into the crowds killing 10 protesters in Sungei Siput and 3 more in Ipoh.[36] In February 1946, the British troops shot dead another 15 unarmed protesters in Labis, Johor.[37] A few days later, they killed 5 more unarmed demonstrators who participated in a protest in Mersing against the slaughter in Labis.[38] The men who aimed into the crowds, their commanders and, ultimately, the BMA”, he asserts, “believed themselves superior and regarded Asian lives as considerably less significant”.[39] Peng makes a pertinent observation of the ghastly episode – how imperialist violence was inherently racialised.

What is rarely mentioned in the historical narratives around British colonial rule is the immense power that planters had in colonised Malaya. Chin Peng explains how they used that power to protect their positions and interests:

“They demanded the imposition of martial law. They had histories of exploiting workers and hiring thugs to break up strikes on their plantations. Many of them were ex-servicemen, demobbed from British World War II units. They had broad experience in military matters. In post-war Malaya they were armed; they surrounded themselves with paid thugs; they drove in armoured cars”.[40]

Imperialist Propaganda to Delegitimise Popular Uprising Against Violent War

It is important to emphasise that the “Malayan Emergency” was a misnomer that the British used to mask the intensity of the 12-year violent war it waged against Malayan insurgents to strengthen its grip on the Malayan peninsula following Japan’s surrender in 1945. Additionally, calling it a war would have invalidated British businesses’ insurance policies.[41] The misnomer was useful for demonising the legitimate armed struggle led by the CPM. It also justified branding members of the party as “communist terrorists” and that was how, as Chin Peng points out, they were “dismissed in the books that touch on that grim and gruesome time”.[42] The early direction for British government public statements testifies to this devious tactic. As the Colonial Office’s Assistant Secretary of State, J. D. Higham demanded: “On no account should the term ‘insurgent’, which might suggest a genuine popular uprising, be used”.[43] Writing to Commissioner Malcolm MacDonald in Singapore in August 1948, Arthur Creech-Jones disclosed that the Atlee Labour government intended to conduct “a vigorous counter-attack on communist propaganda both at home and abroad” to refute the assertion that the “present troubles in Malaya arise from a genuine nationalist movement of the people of the country”.[44] This tactic employed by the British consequently concealed its acts of violence not only right after its reoccupation of Malaya in 1945 but also during the 12-year counter-insurgency war.

Agent Orange First Used in Malaya

Britain was the first country to use a herbicide that contained the deadly contaminant dioxin, similar to what became Agent Orange, in its attempt to starve and wipe out Malayan insurgents in the early 1950s. British troops sprayed crops and roadside verges with the chemicals sodium trichloroacetate (STCA) and Trioxone that have devastating effects. The herbicide could cause disfiguring diseases, cancer, and congenital abnormalities in embryos at low doses.[45] In December 1951, the British colonial state purchased 200 tonnes of STCA from the United States and 80 tonnes of STCA from Sweden.[46] It spent approximately $1.4 million in January 1952 to purchase another 250 tonnes of STCA and 10,500 gallons of Trioxone which were to be used in “large-scale roadside spraying in Malaya” scheduled for the following month.[47]

Concentration Camps

The British also used concentration camps known as “new villages” – another misnomer – which were similar to Japan’s “fortress villages”.[48] The use of these camps was introduced in 1950 by Director of Operations Harold Briggs – the same man in charge of the chemical warfare – to punish hundreds of thousands of people whom the British referred to as “squatters”[49] for supplying food to the CPM during the war. The policy referred to as the “Briggs Plan”, Chin Peng writes, “began isolating us so dramatically from our mass support”.[50] The CPM was consequently confronted with a serious crisis of survival as the squatter communities were detained in barbed-wire camps and subjected to constant searches, interrogations and restrictions on their movement.

Mutilation of Dead Bodies

Another heinous act of violence committed by the British colonial state revealed in My Side of History is the mutilation of dead bodies – a war crime that the state tried to cover up. When the London communist newspaper, The Daily Worker put a photo of a Royal Marines commando posing for the camera, holding the decapitated head of a CPM guerrilla fighter on its front page on April 28, 1952 with the headline “This is the War in Malaya”, an Admiralty spokesman in London was quick to dismiss the image as fake. Similarly, mainstream British newspapers called what was exposed in The Daily Worker a communist trick.[51] While British officials were scurrying to hide the truth, the soldier captured in the photo was identified and he admitted to having committed the act.[52] A former Malayan police officer subsequently confirmed that “it is not an uncommon practice, in the Malayan Police, to bring in the heads of killed bandits for identification”.[53] Legal advice regarding the case was issued to the Admiralty and it warned that “there is no doubt that under International Law a similar case in wartime would be a war crime”[54]

In a blatant display of disregard for human life, Director of Operations Gerald Templer, who was in charge of the revamped anti-insurgency campaign, justified the brutal policy and argued for its continuation. It should be noted that this man was appointed by the government led by Winston Churchill. The CPM, on the other hand, adhered strictly to Mao Tse Tung’s guerrilla warfare principles on the treatment of prisoners. The CPM’s High Command issued specific directives on this matter where all its units “were instructed to treat captured enemy forces humanely”.[55] Additionally, the CPM Central Committee issued a resolution on October 1, 1951, prohibiting the targeting of civilians.[56] Chin Peng emphasises that on no occasion did he ever receive a report saying that his army had committed inhumane acts against its captives.[57]

The Unfinished Revolution

The analysis offered by Chin Peng, the man who not only lived through this turbulent time but also resisted the dehumanising conditions it engendered, could not be more necessary. It provides a comprehensive view of the enormity of violence enacted by Britain that necessitated revolutionary action – a historical fact that often falls victim to institutionally enforced silencing, erasure, and distortion. What makes My Side of History urgent is the way in which it resurrects the deeply buried memory of not only the violence of the coloniser but also the historical acts of the colonised who confronted that violence head on while struggling under the weight of poverty, hunger, and racism. Only by confronting this memory can we start to see with clarity the workings of colonialism and other interlocking systems of oppression such as racism and capitalism, and comprehend the fact that the formal independence negotiated between the British colonial state and the Malayan comprador class did not, as Ahmad Boestamam warned in the 1946 Political Testament of API, constitute genuine independence. Chin Peng’s autobiography remains relevant to modern-day Malaysia as it reminds us of the unfinished revolution and the urgency to revisit its necessity.

Fadiah Nadwa Fikri is a PhD candidate at the Department of Southeast Asian Studies, National University of Singapore, studying resistance to British colonialism in Malaya. Her research interests include decolonisation, transnational solidarity, and Third World feminisms.

[1] Chin Peng, My Side of History (Singapore: Media Masters Pte Ltd, 2003).

[2] CO 1022/152

[3] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 5.

[4] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 3.

[5] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 3.

[6] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 4.

[7] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 11.

[8] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 11.

[9] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 11.

[10] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 26.

[11] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 11.

[12] CO 1022/152.

[13] He replaced former Secretary General Lai Te, who was found to be an agent of Japan, France, and Britain. Lai Te was executed in Thailand after absconding with the CPM’s funds.

[14] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 34.

[15] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 35.

[16] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 49.

[17] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 34.

[18] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 34.

[19] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 35.

[20] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 49-50.

[21] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 57.

[22] The Straits Settlements was a British crown colony comprising four trading centres: Penang, Singapore, Malacca, and Labuan.

[23] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 135.

[24] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 135.

[25] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 135.

[26] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 141.

[27] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 141.

[28] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 141.

[29] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 141.

[30] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 141.

[31] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 141.

[32] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 141.

[33] CAB 129/25, CP(48) 171.

[34] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 142, 222. The killing of the planters was not authorised by the CPM’s Central Committee.

[35] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 142.

[36] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 142.

[37] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 159.

[38] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 159.

[39] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 142.

[40] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 511.

[41] CO 717/176/1.

[42] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 10.

[43] Quoted in Chin Peng, My Side of History, 247.

[44] Quoted in Chin Peng, My Side of History, 247.

[45] New Scientist, 19 January 1984, 6.

[46] New Scientist, 19 January 1984, 6.

[47] New Scientist, 19 January 1984, 6.

[48]The Japanese used concentration camps in Manchuria in the 1930s to break people’s connections with guerrillas.

[49] The British referred to them as “squatters” to justify their being forcibly removed from their homes and sent to concentration camps.

[50] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 299.

[51] Quoted in Chin Peng, My Side of History, 302.

[52] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 304.

[53] Quoted in Chin Peng, My Side of History, 304.

[54] Quoted in Chin Peng, My Side of History, 304.

[55] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 304.

[56] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 511.

[57] Chin Peng, My Side of History, 309.