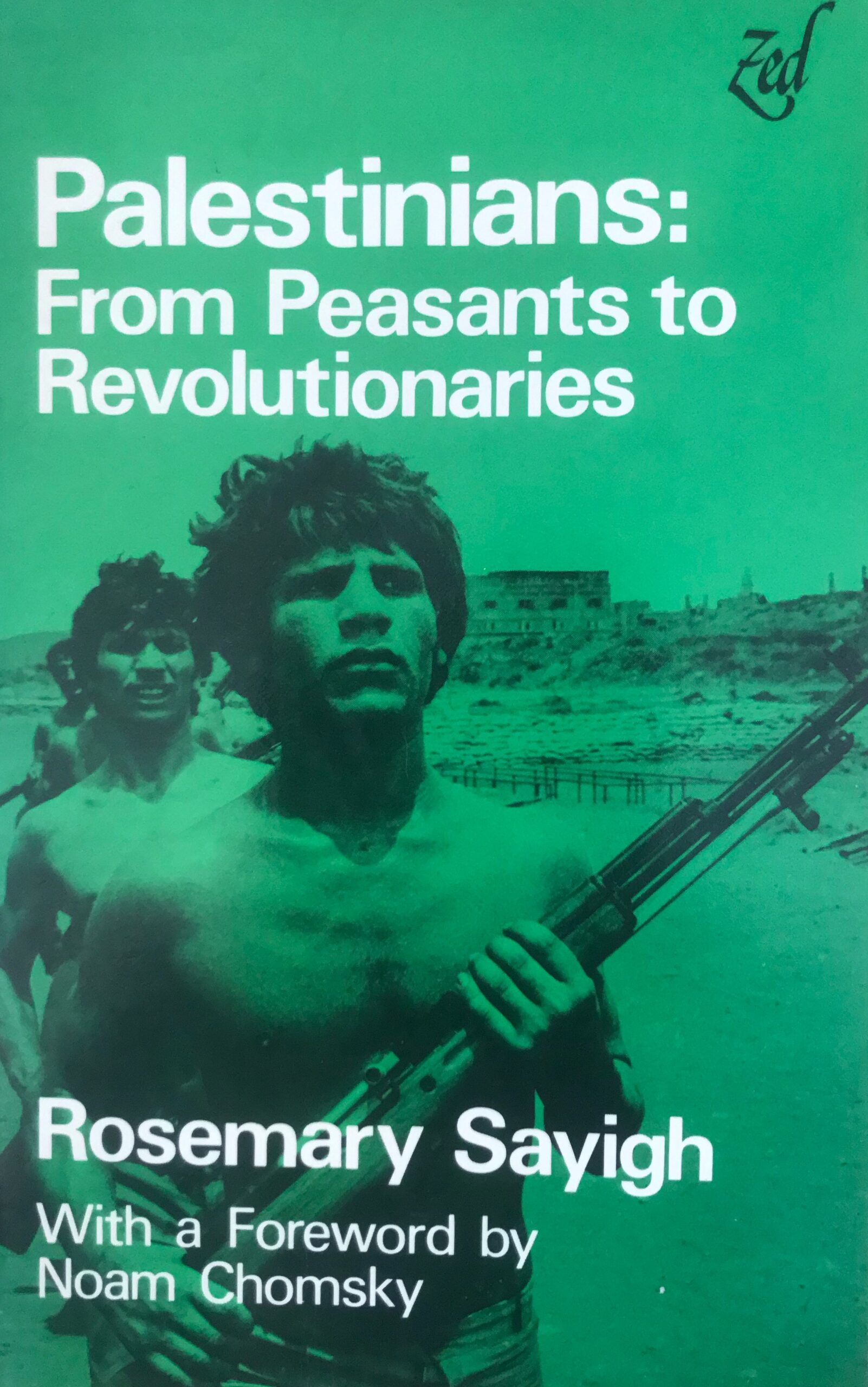

Rosemary Sayigh calls her 1979 book, Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries, an ethno-history. The description is accurate. Sayigh does both ethnography and historiography. It’s not certain whether the book rightly belongs to a single disciplinary category, though. It’s an intimate study of a national community without any pretense of objectivity, which Sayigh rejects out of hand as a colonialist paradigm, professing instead a desire to highlight “the anonymous voices of the Palestinian masses”.1Rosemary Sayigh, Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries (Zed Books, 1979), xxiii. She is interested in telling the story of Palestinians through their own voices and experiences. Even today, over four decades later, this straightforward methodology feels slightly heretical in relation to the restrictive norms of Middle East Studies.

For Sayigh, the book represents a long acculturation into a foreign culture. Born and raised in the United Kingdom, she married Palestinian economist Yusif Sayigh in 1953 and moved to Beirut, where she soon found herself involved in advocacy work for Palestinian refugees. Daily visits to refugee camps eventually became overnight stays and Sayigh cultivated deep relationships with the camps’ rank-and-file. She earned an MA from the American University of Beirut and much later a PhD from York University in the UK. Despite the fact that From Peasants to Revolutionaries was well-received and would soon be considered a classic, Sayigh had difficulty in finding steady academic employment in Lebanon. Subsequent advocates of the Palestinian cause would face the same problem.

It isn’t a stretch to say that the book became a classic precisely because it shuns conventional methodologies. Sayigh hints at a less traditional vision in the preface, noting that she wanted to produce a “people’s history, not official history… concerned not with great events or leading figures, but with ordinary people’s perceptions of these events, and with the ways they have transformed the lives of those classes of Palestinian—peasants, workers and the small bourgeoisie—who had no cushion between them and the Disaster of 1948”.2Sayigh, xxiv.

Palestinian society since 1948 has been scattered and sometimes isolated, with its various “branches” frequently unable to interact. The Palestinians of the Gaza Strip, for instance, are systemically disconnected from those of Lebanon, only a short distance up the Mediterranean coast. (Dozens of other such disconnections exist.) These divisions have created distinct economies and political cultures, which can result in tension among various segments of Palestinian society. Yet the divisions also deepen a sense of shared identity that’s oriented around the homeland. Returning to Palestine is a collective aspiration.

Writing about the Palestinian nation can be a serious challenge because of this disaggregation. What is true of Palestinians in the Gulf States may not hold for Palestinians in North America. Sayigh, however, expertly delivers a narrative of post-Nakba Palestinian life that is both specific and universal. From Peasants to Revolutionaries speaks to a wide-ranging national identity by exploring the sensibilities of a particular diasporic community, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. Sayigh achieved this because Palestine exists in the souls of its descendants as an inexorable lodestar, an always-present emblem of an unforgotten past and the endpoint of an imminent, hard-fought future. That’s how her subjects present the nation—as a physical space, as a lost paradise, as a nostalgic geography—and she honors their words.

Oral histories pepper the book and offer powerful testimonies about the refugees’ devotion to Palestine. Here, for example, Z.K., one of the refugees whose story Sayigh transcribes, reflects on the profound desire to return home:

When we left the village [of al-Sha’b], my paternal and maternal grandfather was taken by the Jews and thrown out to Jordan, he and two of his sons. Two other of my uncles died on the way, near Jenin, but my grandfather, who was by now about 110 years old, went on to Aleppo where he had some relations with whom he stayed for a while, and then he joined us in Baalbeek [camp]. It was very cold in Baalback for an old man, so we returned to Tyre. There, he decided to go back to Palestine. My father tried to convince him that he’s an old man, and that he can’t make it. That was in 1950. But he insisted on going, and without telling anyone he bought a donkey and hired a guide, and he got back to Palestine and reached our village.3Sayigh, 89.

The stories Sayigh gathered are filled with regret and longing, with some of the refugees proclaiming that if they could go back in time, they would choose to die rather than leave their villages. R.M. still suffers deep frustration:

One of the political errors of our leadership was that they didn’t prevent evacuation. We should have stayed. I had a rifle and a Sten gun. My father told me, ‘The Zionists are coming, you know what they do to girls, take your two sisters and go to Lebanon.’ I said, ‘I prefer to shoot my sisters, and shoot you all, and keep the last bullet for myself. This would be better than leaving’.4Sayigh, 90.

Resistance Forms in Lebanon

The Palestinians of Lebanon have had an enormous influence on Palestine’s national liberation movement (and also on Palestine’s cultural accomplishments). In addition to hosting the PLO for many years, Lebanon was home to hundreds of notable poets, guerrillas, artists, and scholars. Despite their difficult circumstances—confinement to overcrowded camps, legalized employment discrimination, poverty, statelessness, racial acrimony—the Palestinians of Lebanon created a dynamic political and artistic culture. Proximity to the homeland informed their tenacity.

Sayigh conducted her research during the first stages of Lebanon’s civil war (1975-1990), which added greater depth to the project. The war intensified the sense of foreignness Palestinians have been made to experience in the country (legally and socially). A recurring theme in the book is that while Palestinians will fight for better living conditions in Lebanon, residing there won’t suffice as a long-term proposition. It’s not Palestine. Returning home is the first and last priority. Home represents stability. Home is indivisible from personhood. Home is the precondition of existence. So-called host countries promise war and instability. Even in the better times, they cannot ameliorate the loneliness of exile. Such is the Zionist entity’s terrible impact on the region. It is an ever-expanding repository of destruction. Having brought massive chaos and suffering to at least two continents, the Zionist entity isn’t merely the material expression of the Palestinian’s agony; it is the obverse of the Palestinian’s primary aspiration.

Hence the basis for a dramatic history of resistance. Resistance comes in many forms, but Sayigh is concerned with the revolutionary variety. Her fieldwork isn’t limited to interviews; she chronicles life embedded among Palestinian refugees. She also examines how Palestine, on the eve of the Zionist project (and throughout the first half of the 20th century) was a largely agrarian population—a “peasant society,” in Sayigh’s words—and how “in spite of Jewish immigration, and the growth of industry and urbanization, by 1948 two-thirds of Palestine’s Arab population was still rural. There is thus good reason to regard Palestinian society as a peasant society, and its struggle for liberation a peasant-based struggle”.5Sayigh, xxiv.

Sayigh traces the development of Palestinians from a rural proletariat into urbanized communities engaged in a wide range of professions, teaching in particular. This development represents the story of Palestine’s revolutionary sensibilities. The society evolved, but the peasant values survived. Palestinians in Lebanon would become a technocratic fellaheen, innovators of a vanguard playing on the imagination of every downtrodden community that took up arms against its oppressor.

Sayigh’s notion of a peasant society is complex. She speaks of Palestinians across all economic strata, giving special attention to the descendants of the farmers and workers who ended up in Lebanon in large numbers (moneyed Palestinians and Christian Palestinians could often escape the camps). The ethnographic features of her analysis proffer a coherent framework for understanding a rapid, almost impossible societal transformation. The main conclusion is that Palestinian resistance didn’t arise from urban centers in conditions of leisure or abundance. Peasantry, as Sayigh often reminds us, suggests intimacy with land. It’s not possible to comprehend Palestinian resistance without a concomitant appreciation of the nation as a physical reality. The idea of Palestine derives life from the specific landbase on which the Zionist entity was established; Palestine cannot be replicated in any other geography

Sayigh develops her argument by focusing on individual villages, combining archival research with oral history to piece together a comprehensive narrative of Palestinian life in states of dispossession. She likewise gives a thorough overview of family structures and social conventions, which played a role in the Nakba and its aftermath. The guiding principle was communal self-sufficiency: “For Palestinian peasants, the city had never been economically indispensable. They looked to the cities for leadership, as the crisis generated by Zionist immigration intensified; but until their final ‘cleaning’ from their land in 1948, the villagers still produced the bulk of their foodstuffs”.6Sayigh, 24. Sayigh devotes a chapter to this “cleansing” and presents a damning indictment of Zionism, whose proponents committed massacres throughout the Palestinian countryside with the explicit aim of removing its inhabitants and taking their land.

This terror arose from a brutal strategic calculus: “An atrocity particularly calculated to horrify Arab peasants was the cutting open of the womb of a nine months’ pregnant woman. This was the clearest of messages warning them that the Arab code of war, according to which women, children and old people were protected, no longer held good in Palestine”.7Sayigh, 77. The displaced populace had no choice but to become revolutionaries. Any other approach would have implicitly forfeited their claim to the land. As Sayigh’s brother-in-law, Fayez, contended when extolling the virtues of Palestinian resistance, “[r]ights undefended are rights surrendered. Unopposed and acquiesced in, usurpation is legitimized by default.” Because of the geopolitical forces invested in the Zionist entity’s existence, Palestinian nationalism is necessarily a revolutionary project. With great care and empathy, Sayigh traces its development from the countryside to the overcrowded camps of Beirut.

The Situation Changes

From Peasants to Revolutionaries isn’t exactly a forgotten text, but it’s closer to obscurity than it deserves. The second edition, which I am using for this review, was published in 2007 and sells for a price that suggests obsolescence. And yet, whatever the barriers to access, it should be read. (You can skip the two introductions by Noam Chomsky. He’s only there for decoration.) The book is compact and lucid. Sayigh’s theoretical rigor rarely leads to esoteric language. One would feel comfortable putting From Peasants to Revolutionaries into the hands of a high school student.

I try to rein in my nostalgia when it comes to classics of scholarship and literature. There’s always a whiff of sanctimony in ruminations beginning with some version of “back in my day,” so I don’t want to denigrate current writing about Palestine, which is often sharp and innovative. Yet the general sensibility of intellectual work feels different. I imagine that, with some notable exceptions, the change of sensibility has less to do with individual proclivities than with structural limitations. I don’t know that people with professorial aspirations these days could afford to publish something like From Peasants to Revolutionaries—or even attempt a project with such a clear point of view. Not in English, anyway. It would be a sure path to tenure denial: not rigorous enough, subjective, polemical, dubious sourcing, published by a nonacademic press—everything, basically, that makes a history book pleasant to read, rather than formulaic deadweight calibrated to establishment sensibilities. Sayigh’s own experience in academe validates any such timidity.

Perhaps the feeling of difference arises from the fact that conditions in Palestinian society have changed since Sayigh first started gathering research. Post-Oslo, the revolution was largely subsumed by diplomacy and the attendant shift of activism from armed struggle (or at least confrontation) to NGOs and cultural and religious organizations, many of dubious provenance. Revolutionary sentiment remains—the peasant values that Sayigh identifies—but it’s no longer one of the defining features of Palestine’s national movement. Major political parties have either embraced neocolonialism or wield little influence. The camps in Lebanon are impoverished and surrounded by the Lebanese military. A bloated class of mendacious functionaries interjects itself into everything, including (or especially) the public purse. In the United States, a new class of activist, invariably affiliated with the Democratic Party, barters Palestinian liberation for the cheapest possible return: individual clout. Arab states are lining up to normalize with the Zionist entity (while extracting no real concessions—the sole purpose is to further enrich the ruling class); the countries still supportive of Palestine suffer unending imperialist aggression. Palestine’s civic sphere remains vibrant, but Basel al-Araj’s fate portends a very difficult path for those who attach themselves to the revolutionary tradition.

In turn, From Peasants to Revolutionaries is more important than ever. We need less accommodation to the logic of Western diplomacy, to the superficial comfort of white-collar decorum, and more focus on the peasant values that encompass an uncompromising vision of the homeland, intimate and indivisible. The book isn’t merely an artifact of a bygone period, but a living document reminding today’s activists and scholars that the struggle for Palestine’s liberation is a spectacular phenomenon, relentless and unambiguous and often paid for in terrible acts of bloodletting.

We ought to keep the document alive, for the history Sayigh so vividly describes is only one arc in an uncompleted revolution. The text cannot be finished until Palestinians evolve from revolutionaries to repatriated citizens.

Steven Salaita’s latest book is Inter/Nationalism: Decolonizing Native America and Palestine. His personal website can be found here.